This article was originally published by Tyler Durden at ZeroHedge.

Two months ago, we noted the first Arab Spring 2.0 incident when, as a result of soaring food, energy (and everything else) prices, thousands of angry Iraqis took to the street to protest. Needless to say, their complaints did not get much traction, and in the meantime food prices have only exploded to fresh record highs, far surpassing the levels hit in 2011 when riots against, you guessed it, food prices toppled most MENA political regimes (not without some CIA backing).

And as food prices keep rising, the protests across poor nations keep escalating, and on Thursday protests broke out in Iran leading to at least 22 arrests, after the government cut subsidies for food, sending prices through the roof as authorities braced for more unrest in the following weeks, Fox News reports.

In videos shared on social media, protesters can be seen marching through Dezful and Mahshahr in the southwestern province of Khezestan, chanting “Death to Khamenei! Death to Raisi!” referring to Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi has promised to create jobs, lift sanctions, and rescue the economy.

Iranian state media has not publicly addressed the protests, but they have been covered by the National Council of Resistance of Iran, an opposition group. Footage shared by the NCRI shows protesters setting fire to a Basij military base in Jooneghan, a city in the Central District of Jooneghan county.

“Every so often we see these types of protests in Iran. Each time it is under a different premise – the price of eggs, the price of gas, the price of bread, but the underlining message which is supported by the slogans heard throughout the demonstrations is the same; they are protesting the entirety of a brutal regime,” Lisa Daftari, Iran expert and editor-in-chief of the Foreign Desk, said in a statement.

“It is also evident in the fact that these protests are no longer just contained to Tehran, the capital city, and other urban areas. We are seeing protests throughout the country in urban and rural areas and throughout the very vast and diverse Iranian population.”

Daftari is right, and not just about Iran (and Iraq), but also Sri Lanka, where protesters angry at the soaring prices of everyday commodities including food, have burned down homes belonging to 38 politicians as the crisis-hit country plunged further into chaos, with the government ordering troops to “shoot on sight.”

Police in the island nation said Tuesday that in addition to the destroyed homes, 75 others have been damaged as angry Sri Lankans continue to defy a nationwide curfew to protest against what they say is the government’s mishandling of the country’s worst economic crisis since 1948.

The Ministry of Defense on Tuesday ordered troops to shoot anyone found damaging state property or assaulting officials, after violence left at least nine people dead since Monday, according to CNN; it is unclear if all of the deaths were directly related to the protests. More than 200 people have been injured.

The nation of 22 million is grappling with a devastating economic crisis, with prices of everyday goods soaring, and there have been widespread electricity shortages for weeks. Since March, thousands of anti-government protesters have taken to the streets, demanding that the government resign.

The military had to rescue the country’s outgoing Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa in a pre-dawn operation on Tuesday, hours after he resigned following clashes between pro-and anti-government protesters. The military was called after protesters twice tried to breach the Prime Minister’s Temple Trees private residence compound overnight, a senior security source told CNN.

Rajapaksa’s resignation came after live television footage on Monday showed government supporters, armed with sticks, beating protesters at several locations across the capital, and tearing down and burning their tents. Dozens of homes were torched across the country amid the violence, according to witnesses CNN spoke to.

Armed troops were deployed to disperse the protesters, according to CNN’s team on the ground, while video footage showed police firing tear gas and water cannons.

It remains unclear if the curfew and the Prime Minister’s resignation will be enough to keep a lid on the increasingly volatile situation in the country.

Many protesters say their ultimate aim is to force President Gotabaya Rajapaksa — the Prime Minister’s brother — to step down, something he has so far shown no sign of doing.

* * *

Going back to the same soaring food prices which tend to have quite a deadly and destabilizing impact on the world’s mostly poor nations, the ones who have no social safety net, Goldman recently published a Q&A on global food inflation (available to Professional Subscribers in the usual place), in which the bank look at the consequences of the global food crisis which is only getting worse by the day. Below we excerpt several sections from the Q&A:

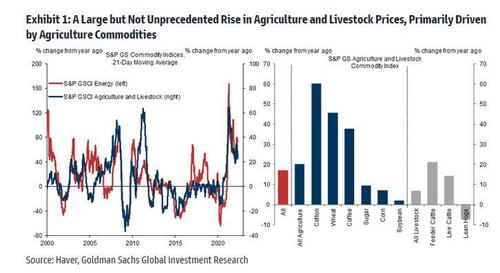

Q. How large is the shock to global food prices?

A. Quite large but not unprecedented, and less large than the shock to energy prices.

Our GSCI Agriculture and Livestock index has increased by 17% over the past year and by 75% since the start of the pandemic (Exhibit 1, LHS). These moves are similar to those in 2008 and 2012 but less large than the current rise in energy prices. Our GSCI Energy index has increased by 70% over the past year and by 110% since the start of the pandemic. Agriculture commodities have seen sharper price gains than livestock commodities with increases in the GSCI Agriculture Index of 21% over the last year and 90% since early 2020 (Exhibit 1, RHS). Wheat prices have risen particularly sharply since 2020H2 due to unfavorable weather conditions and higher input costs.

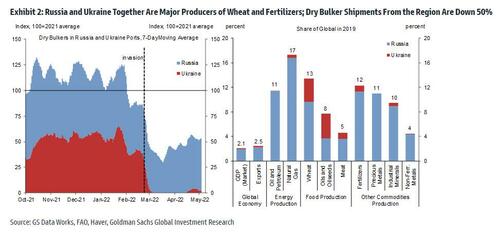

Q. How is the war in Ukraine affecting global food prices and what is the outlook?

A. War-related supply disruptions have contributed to the rise in wheat and oilseed prices. Our commodity strategists expect wheat prices to rise up to 15% over the next few months, with upside risk for the next year.

The war in Ukraine has severely disrupted shipments of grains and oilseeds from the region. Combined dry bulk shipping activity in Russia and Ukraine ports has dropped by 50% compared to the 2021 average (Exhibit 2, LHS). The war is also likely to depress future production by disrupting Ukrainian spring planting of corn and sunseed and tillering of wheat. Russia and Ukraine together account for 13% and 8% of global wheat and oilseeds production, respectively (Exhibit 2, RHS), with CEEMEA countries especially relying on food imports from the region. As a result, wheat and oilseed futures have increased by 30% and 25% since the invasion, respectively, from already high levels.

Although the region plays an important role in global food production, Russia’s share in global energy production is even higher. This helps to explain why energy prices have generally risen more since the invasion than food prices.

Q. How does the hit from higher food prices to consumer purchasing power compare across economies?

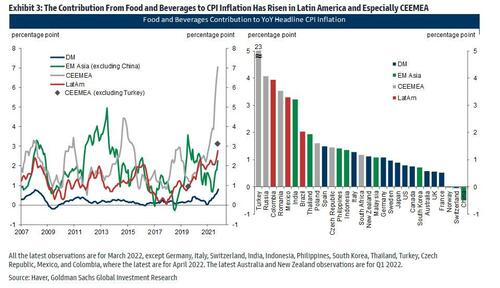

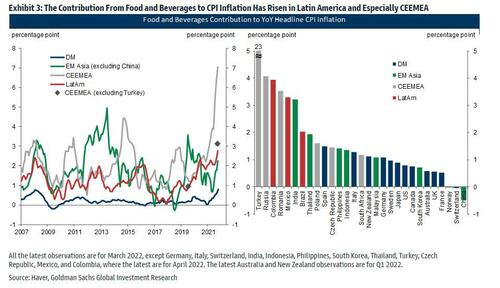

A. The contribution from food and beverages to year-over-year headline CPI inflation is the largest in CEEMEA (7.1pp, PPP-weighted average), followed by Latin America (2.8pp). The contributions are less large in EM Asia excluding China (2.3pp), in DMs (0.8pp), and China (-0.5pp).

The food contribution to inflation is larger in EMs than DMs, although it is not unprecedented for Latin America and EM Asia (excluding China). While less elevated than in comparison to EMs, the current DM food contribution of 0.8pp is the highest on record, going back to 1996 (Exhibit 3, LHS).

By country, the food contribution is the largest in Turkey (23pp) and Russia (4pp), but negative in China at -0.5pp (Exhibit 3, RHS). The very large contribution in Turkey reflects sharp currency depreciation, reliance on imports of cereal, oilseeds, and oils from Russia and Ukraine, and droughts. The large food contribution in Russia partly reflects recent war-triggered demand from the hoarding of non-perishable food. Finally, food deflation in China reflects an oversupply of hogs.

* * *

Q. What are the key implications of elevated food inflation for financial markets?

A. Upward pressure on EM policy rates and negative effects on credit and FX markets in frontier economies facing sharp “food-only” terms of trade deteriorations.

Further food price increases would likely put upward pressure on global and especially EM policy rates given the already very elevated inflation levels, and often less well-anchored inflation expectations. The impact on DM policy rates should be more limited smaller, although food prices also influence DM short-term inflation expectations.

High food inflation can also have negative effects on credit and FX markets in frontier economies facing sharp terms of trade deteriorations. “Food-only” terms of trade have worsened in about 80% of the EMs this year. Using data on these terms of trade moves, food CPI weights, and fiscal balances, our EM strategists conclude that frontier sovereign credit markets in Egypt, Ghana, Tunisia, and Morocco are particularly vulnerable to food inflation shocks. Rising food inflation may also contribute to sociopolitical unrest in lower-income countries, as is currently the case in Sri Lanka.

More in the full report available to professional subs.