This article was originally published by Ethan Huff at Natural News.

Scientists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have come up with a new microneedle vaccine technology that allows for small vaccine patches to be created on demand using three-dimensional (3-D) printing machines.

Dr. Ana Jaklenec, who co-authored a study about the technology, stated that the plan is to use these 3-D vaccine printing machines in the Third World to mass-vaccinate poor people without the need for refrigeration and other traditional vaccine storage and transportation methods.

“We could someday have on-demand vaccine production,” Jaklenec said in a press release, explaining that 3-D printed vaccine patches can be stored at room temperature for months at a time.

“If, for example, there was an Ebola outbreak in a particular region, one could ship a few of these printers there and vaccinate the people in that location,” she added.

(Related: After the launch of covid, Bill Gates announced plans to mass-inject the world using quantum dot tattoos with hidden coronavirus “vaccines.”)

Each patch, Jaklenec further explained, contains vaccine “ink” that was injected into molds by a robotic arm. A vacuum chamber is then used to draw the ink to the individual tips, palisades, or the patch.

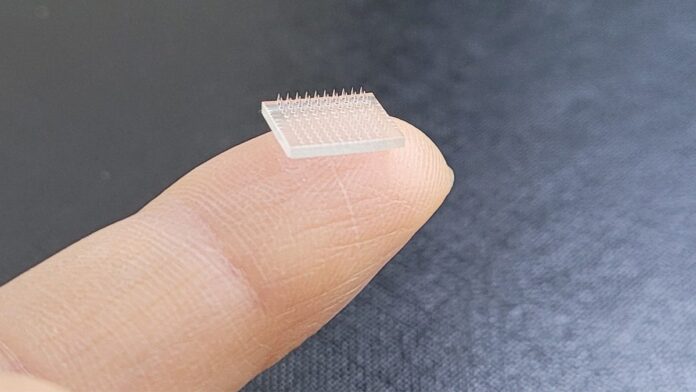

“The resulting patches, about the size of a thumbnail, contain hundreds of microneedles that enable the vaccine to dissolve,” reported Study Finds. “The needles’ tips dissolve under the skin, releasing the vaccine.”

According to Dr. John Daristotle, the study’s lead author, it was the launch of covid that ultimately led to these efforts to “incorporate RNA vaccines into microneedle patches.”

The goal is to create these vaccine patches for all sorts of conditions, including polio, measles, and rubella. Just slap on a patch and voila: instant vaccination with no need for a traditional injection.

The ink in these patches contains RNA molecules encapsulated in lipid nanoparticles, which are used for maintaining stability of the solution for extended periods of time.

After the molds are filled, it takes 24-48 hours for them to dry. Using the current prototype, the ink volume is enough to produce 100 patches in two days, though scientists hope to increase capacity over time.

The first ink created with RNA encodes for luciferase, a fluorescent protein derived from the name Lucifer, which means light-bearer. In essence, Big Pharma wants to inject everyone with Lucifer by sticking microneedle vaccine patches on people’s bodies.

“Under all storage conditions, the patches induced a strong fluorescent response when applied to mice,” reports explaining how luciferase works.

“In contrast, the fluorescent response produced by a traditional intramuscular injection of the fluorescent-protein-encoding RNA declined with longer storage times at room temperature.”

In tests, mice given the microneedle luciferase patches exhibited the same response as those given an RNA injection with a traditional needle.

“This work is particularly exciting as it realizes the ability to produce vaccines on demand,” said Joseph DeSimone, a professor of translational medicine and chemical engineering at Stanford University, who was not involved in the research.

“With the possibility of scaling up vaccine manufacturing and improved stability at higher temperatures, mobile vaccine printers can facilitate widespread access to RNA vaccines.”

Jaklenec further explained that she and her team hope to produce other types of vaccines using the same technology, including those made from proteins and inactivated viruses.

“The ink composition was key in stabilizing mRNA vaccines, but the ink can contain various types of vaccines or even drugs, allowing for flexibility and modularity in what can be delivered using this microneedle platform,” she said.