Red dot or LPVO? Spend five minutes in any gun store, forum, or social media group, and you’ll probably hear someone asking this common question about optic choice. Red dot sights are often considered the default — unless you’re still rocking iron sights, you probably already own an RDS, if not several. They offer a quick-to-acquire point of aim and wide field of view with zero magnification. On the other hand, the low-power variable optic (LPVO) is a powerful tool that can help you maximize the capabilities of your rifle through adjustable magnification ranging from 1-4x, 1-6x, 1-8x, or more. However, if you want to get the most out of it, you’ll need to do your homework.

Above: An LPVO, such as the Vortex Razor HD 1-10×24 seen on the 13.9-inch AR I used during the TruKinetics course, can be supplemented by an offset red dot sight (such as a Trijicon RMR). But as you’ll see later in this article, that addition is far from mandatory.

TruKinetics Intro to the LPVO Course

Above: Norman offers advice to a pair of students after moving through a practical course of fire in the Arizona desert.

In an effort to address the pros and cons of the LPVO and learn how to use one effectively on an AR-platform rifle, I signed up for a two-day Intro to the LPVO class from TruKinetics. Founded in 2020 by 23-year law enforcement veteran David Norman, TruKinetics started strong with a focused selection of course offerings and a cadre of instructors with highly-relevant skill sets. For a class focused on LPVO use at distances from 5 to 500 yards, you’d be hard pressed to find a group of three instructors with more real-world experience behind these optics:

- David Norman – 23+ years working law enforcement in Phoenix, AZ, including 13 years of full-time SWAT experience with Special Assignments Unit (SAU); Department of Defense contractor

- Brian Langoliers – retired USMC Scout Sniper, U.S. State Department security contractor, and Phoenix Police SAU sniper

- Todd Besaki – retired Army Ranger, federal agent for the U.S. Department of Energy training teams that escort nuclear materials

Read on for some lessons learned from this course, and how our experiences on the range reshaped our perspective on the value of the LPVO.

Red Dot (+ Magnifier) vs. LPVO

In essence, the LPVO bridges the gap between a red dot sight and a medium-power rifle scope. A quality LPVO offers true 1x magnification (or extremely close to it) and a bright illuminated reticle for close-range targets, as well as the capability to adjust quickly to a higher magnification setting for targets that are further away.

LPVO Advantages

Most importantly, TruKinetics emphasized that an LPVO’s magnification offers enhanced ability to positively identify (PID) a target before choosing to shoot. At extended range with a red dot, you might not be able to determine if the individual you’re looking at is carrying a gun or some other object. That’s critical information, no matter if you’re a member of the military, a law enforcement officer, or a civilian. The LPVO is a potent tool for gathering information, even if you don’t have to pull the trigger. And it allows you to obtain this information from further away — that distance enhances your safety and buys you time to react to any potential threat.

Of course, there are a variety of magnifiers for red dot and holographic sights, as seen on Tom Marshall’s OD green rifle above. These magnifiers can improve extended-range PID capabilities with a red dot, but they’re not without drawbacks of their own. According to the TruKinetics instructors, red dot magnifiers are typically…

- Less versatile than LPVOs — they offer fixed-power magnification with an on-off switch, rather than a range of magnification settings

- Dependent on the battery in a powered red dot, rather than an always-present etched reticle

- Open to dirt, smudges, and other obstructions on four lenses, rather than two on an LPVO

- More complicated to zero, since the magnifier and red dot each have elevation and windage adjustments

- More prone to shifting parallax, since toggling the magnifier adds/subtracts layers of glass

- Less effective under low-light environments or tinted windows, due to poorer light-gathering

As a quick example, if a 1x red dot has acceptable PID capability on a given target out to 100 yards, a dot plus magnifier might offer the same level of PID out to roughly 300 yards. Under the same circumstances, a 1-6x LPVO could offer solid PID out to 400 yards. A 1-10x optic can easily PID targets at 600 yards and beyond. If your rifle and ammunition are capable of remaining effective at that range, why wouldn’t you want an optic that can match their performance?

LPVO Disadvantages

Even though each of the three instructors swears by the LPVO based on decades of professional experience, they weren’t afraid to point out some of the drawbacks of these low-power optics. Here are some of the cons of LPVOs versus red dots, with or without added magnifiers:

- Weight — LPVOs are generally rather heavy, although this has been getting better in recent years. It’s up to you to decide if the extra capabilities are worth a few ounces of added weight.

- Eye Relief — Any magnified optic (including red dot magnifiers) will be more sensitive to the shooter’s eye position than a 1x red dot. This can be overcome by setting up your optic properly and understanding the impact of scope shadow.

- Night Vision Capability — If you need to passively aim while wearing NVGs, it’s not easy with an LPVO. Adding an offset or top-mounted backup red dot sight is a simple solution for NVG users.

- Cost? — At first glance, an LPVO might seem expensive. However, the price of a comparable-quality red dot, magnifier, and two mounts adds up fast, and this often ends up as a wash.

- Training — There’s a bit of a learning curve for newer shooters to feel quick and confident behind an LPVO. More on this later.

For a more in-depth guide to these points, refer to the article “Grudge Match: LPVO vs. Magnifiers” from our sister publication Recoil.

How to Choose an LPVO

So, you’ve decided to buy an LPVO — which one should you get? There are many good choices, but before you spend any money, you should learn what you need. During our class, TruKinetics instructors offered a list of important considerations for buying an LPVO, in order of importance:

Focal Plane – SFP vs. FFP

Second Focal Plane (SFP) and First Focal Plane (FFP) optics both have their place. This discussion could be its own article, so to keep things simple, we’ll summarize:

- SFP optics have reticles that stay the same size regardless of magnification. They’re less expensive, and usually have simpler reticle designs that lend themselves to close-quarters use at 1x. However, SFP reticle markings (subtensions) are only correct at a specific magnification value, so you’ll need to memorize that and avoid intermediate magnification settings if you plan on doing any long-range work.

- FFP optics have reticles that increase in size as magnification increases. They’re more expensive, but no matter what magnification setting you use, the reticle markings will be correct. FFP reticles tend to offer more precise “Christmas tree” markings for long-range use, but can appear more cluttered at 1x. These optics are ideal for users who may need to quickly engage multiple targets at varying distances, especially longer ranges.

Reticle

Your optic’s reticle is extremely important. Consider it carefully before buying! There are four main options:

- Duplex a.k.a. plain crosshairs — These reticles give the user no additional information or measurements, and are not recommended.

- Bullet Drop Compensator (BDC) — This gives a “quick and dirty” point of aim for various distances, but only if you’re using the barrel length and ammo the reticle is designed for. For military- and law-enforcement-issued duty guns with consistent ammo, it makes sense. For civilians who mix and match various brands and weights of ammo, it’s not a good choice.

- Minute of Angle (MOA) — One of the two primary measuring systems, which equates to 1/60th of a degree (or 1 inch at 100 yards).

- Milliradian (MIL a.k.a. MRAD) — The other measuring system, which equates to 1/1000th of a radian (or 1 meter at 1000 meters).

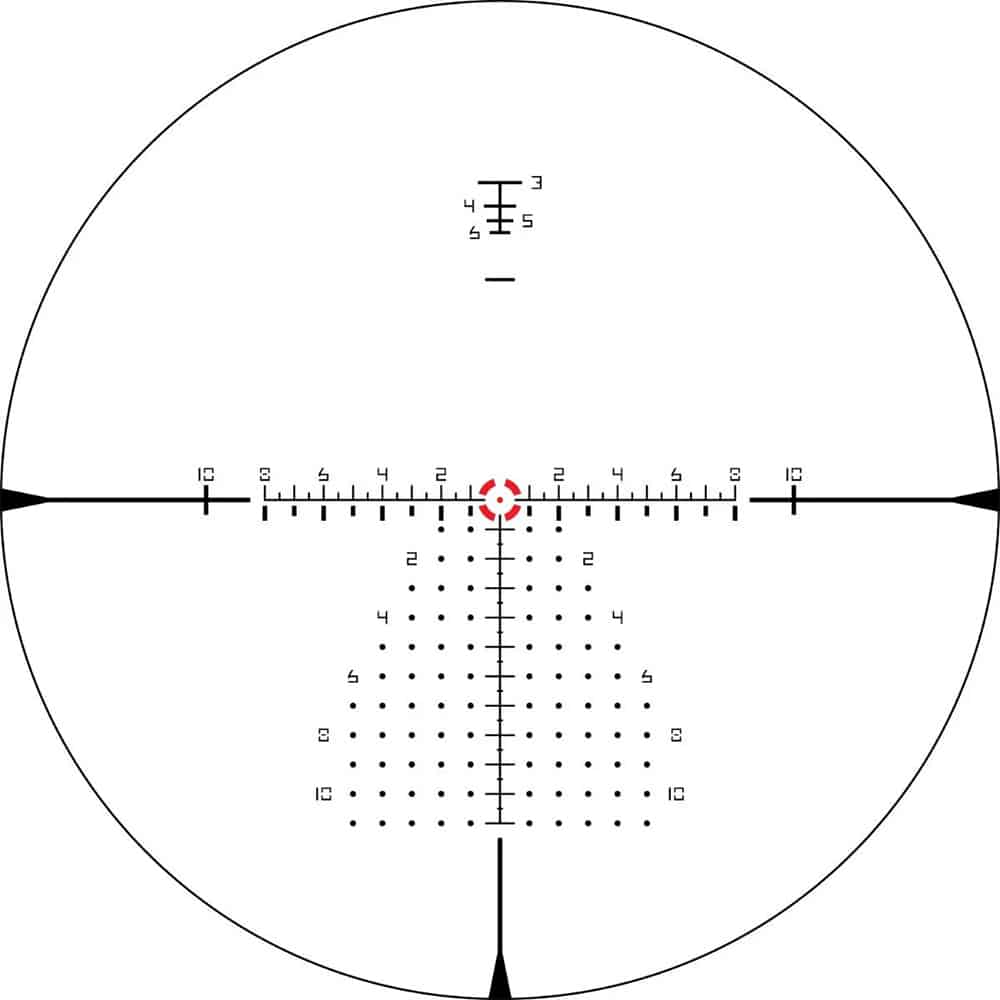

Above: I chose this EBR-9 MRAD reticle for my Vortex Razor HD Gen III LVPO. At full magnification (as pictured) its dotted “Christmas tree” offers clear measurements to hold for wind and elevation at longer ranges.

If you’re trying to decide between MOA and MIL, we’ll refer you to this article from our sister publication Recoil. Basically, both are viable — even the TruKinetics instructors had varying preferences, with two preferring MILs and one MOA. Whatever you do, don’t get an optic that uses both (i.e. an MOA reticle with MIL adjustments) because this gets extremely confusing. One instructor put it bluntly, “sell that sh*t if you have it.”

Lastly, consider your mission before picking an LPVO reticle. Some reticles are great for long-range precision but will appear cluttered at 1x; others are nice and clean at 1x but don’t offer much useful info for long-range use.

Eye Relief / Eye Box

Eye relief is the distance your eye needs to be from the eyepiece to achieve a full image; eye box is the 3D space where your eye can move while maintaining that full image. As mentioned earlier, LPVOs are sensitive to eye/head position, and can produce scope shadow as the eye moves towards the edges of the eye box. TruKinetics recommends LPVOs with “generous” eye box and eye relief of 3 inches or more. This makes it easier to get a consistent sight picture quickly.

Above: Brian of TruKinetics explained scope shadow with this diagram. The arrows indicate point of impact shift — if you see shadow on one side of the optic, the impact of your shots will be “pushed” slightly in the opposite direction.

Trueness of 1x

Ideally, your LPVO should offer a true 1x magnification, or extremely close to it. If the minimum setting is noticeably greater or less than 1x, you may not be able to shoot well with both eyes open, and your brain’s processing of visual information may be slowed.

Illumination

If you intend to use your LPVO in bright environments, look for “daylight bright” reticle illumination. This will help your optic feel more like a red dot sight at 1x. If you intend to shoot in low light environments, your full reticle should be illuminated, not just the center point.

Turret Security

In order to prevent your LPVO’s elevation and windage turrets from turning inadvertently, choose an optic that has locking and/or capped turrets. This will help you trust that your rifle is zeroed every time you need it.

Durability & Track Record

If you need to trust your life to a weapon, choose an LPVO make and model that has a track record of proven durability, preferably in the hands of military or law enforcement users. Research this carefully and do your best to exclude single-user anecdotes.

Magnification Ring

Put simply, the magnification ring should move when you need it to, and stay put otherwise. Many users prefer a throw lever for fast adjustments, but be careful that it doesn’t snag on gear and unexpectedly change the magnification setting.

Above: Another configuration of my rifle included this Leupold Mark 8 LVPO, which features locking turrets rather than removable caps. Also, the magnification ring has a raised tab rather than a large throw lever.

Glass Clarity

It’s not necessary to get too far into the weeds here, but poor-quality glass can lead to “fisheye” distortion near the edges of the image — this can cause parallax shift problems if your eye isn’t centered inside the eye box while shooting. Japanese and German glass tends to be clearer, but Chinese glass has also come a long way in recent years.

Diopter Design

“This is one of the most important and most misunderstood pieces of an LPVO,” said one instructor. The diopter ring on an LPVO must be adjusted to match your eye, and failure to do so can cause a true 1x optic to feel anything but. An improper diopter setting can even cause eye fatigue and headaches. Like the magnification ring, your LPVO’s diopter ring should move only when you want it to.

Weight and Size

How will you use your rifle? If it’s mostly a bench rest gun, a little extra weight is no big deal. If it’s something you’ll carry on a sling for hours or days at a time, every ounce matters.

Above: If you need to run with your rifle or hike long distances, weight is a major consideration, but it should also be balanced with the optic’s features and durability.

…and Finally, Price

The old adage still applies: you get what you pay for. However, be realistic and don’t assume you need the most expensive optic money can buy. As one of the TruKinetics instructors put it, “Buy what you really need, not what someone on Instagram says is awesome.”

For a trustworthy entry-level LPVO, TruKinetics instructors recommended the Vortex Viper PST 1-6×24, which retails for about $600. If you’re looking for something professional-grade, they recommend stepping up to an optic in the $1,000 to $1,500 range, such as an EOTech Vudu, Vortex Razor HD Gen II, or Trijicon Accupoint.

How to Choose a Mount

Above: In this photo, Todd from TruKinetics is installing an EOTech Vudu 1-6×24 LPVO in a Bader Ordnance Condition 1 mount. Note the cantilevered design that places the rail mount near the midsection of the optic.

Much like you’d be foolish to buy a $150,000 Porsche and install the cheapest set of tires you can find, you shouldn’t try to cut costs with your optic mount — it’s where the rubber meets the road. TruKinetics recommends one-piece scope mounts for LPVOs, specifically cantilevered mounts that allow the optic to be mounted further forward on the gun. This ensures the optic can be positioned appropriately while remaining securely attached to the upper receiver (not “bridged” onto the handguard). Make sure you choose a mount that matches your optic’s tube diameter (e.g. 30mm or 34mm).

There are many excellent LPVO mount manufacturers to consider, including LaRue Tactical, American Defense Mfg. (ADM), Warne, Midwest Industries, Geissele, and Badger Ordnance.

Above: Instructor Brian’s rifle is equipped with an EOTech Vudu LPVO in a Larue Tactical SPR quick-detach mount. Its 1.5-inch height offers plenty of cheek weld stability for prone shooting. Brian’s setup also includes a backup Trijicon RMR in a separate 45-degree mount.

Is QD Really Necessary?

Quick-detach functionality is optional, but certainly not mandatory. After all, it’s best practice to avoid removing your optic once it’s zeroed. The likelihood of any quality LPVO failing so catastrophically that it must be removed during a firefight is very low, and if that’s a concern, you should consider installing an offset sight system (45-degree irons or a backup red dot).

Poor-quality QD mounts can come loose unexpectedly, throwing off your zero or even allowing the optic to fall off the gun; high-quality mounts should be just as secure as a bolt-on mount, but you’ll generally pay more for this feature.

Above: While low optic mounts offer a comfortable cheek weld for prone shooting, high mounts make it easier to achieve a clear sight picture in more challenging positions. Each student experienced this firsthand after shooting through the various openings in a plywood VTAC barricade.

How High?

Mount height has a substantial impact on shooting comfort, so you should consider it carefully before you buy. Base your decision on the height measurement in inches, rather than vague terms like “standard height” or “lower 1/3 cowitness.” Here’s a quick breakdown of some common choices:

- 1.2 inches — These mounts are usually designed for traditional hunting rifles, and are too low for most AR-platform applications.

- 1.5 inches — This is the most common height for traditional LPVO mounts. It works fine for many shooters, and offers a very stable cheek weld against the stock, but it can be a little tougher to acquire a sight picture in compromised shooting positions.

- 1.7 inches — Another popular choice, and a nice middle ground for most shooters.

- 1.9 inches — These taller mounts offer a “heads-up” shooting position, which some shooters find faster and more comfortable. However, there’s a trade-off: it may lead to neck strain while shooting from the prone. Muzzle awareness is also important with tall mounts, since it becomes easier to inadvertently shoot the edge of a barricade.

- 2.0+ inches — These are often referred to as night-vision-height mounts, and they’re more common for red dots than for magnified optics. They have some substantial drawbacks for LPVOs, including difficulty establishing a solid cheek weld against the stock (especially in the prone) and hold-over issues at close range.

In the next part of this series, we’ll cover how to properly install your LPVO on your rifle, as well as some TruKinetics training tips for close-range and long-range shooting with an LPVO.

Related Posts

The post Mastering the LPVO: Part 1 – Low-Power Variable Optic Buyer’s Guide appeared first on RECOIL OFFGRID.