When news of a dam malfunction on Montana’s Madison River broke in early December, the Western trout fishing world watched in horror as photographs showed a rapidly dewatered stretch of river with fish left high and dry on the rocks. This would have been a troubling sight on any waterway, but it was particularly appalling to see it happening on the most beloved and heavily fished river in what is arguably the troutiest state in the country.

The immediate effects of a failed component in one of Hebgen Dam’s spillway gates were obvious. Around 1 a.m. on Nov. 30, the river flowing below the dam suddenly dropped from roughly 650 cubic feet per second to an all-time recorded low of less than 250 cfs. This drop was especially noticeable in the stretch between Hebgen and Quake Lakes. Entire channels dried up, spawning redds and freshly laid trout eggs were exposed, and the rocky banks of the river sprawled out into all but the deepest pools. Meanwhile, locals rallied to save hundreds (if not thousands) of stranded fish as they sounded the alarm and alerted authorities. Flows were restored approximately 48 hours later, and the upper Madison appeared to return to normal.

It will be years before we can fully comprehend the damage that was done during the 2021 Hebgen Dam debacle, and there will likely be long-term environmental effects on the upper Madison River and the world-class fishery it supports. But one thing is for sure: It could have been a hell of a lot worse.

“A Shot to the Gut”

John McClure has been a guide on the Madison River since 2005, and he manages the fly shop at Galloup’s Slide Inn, a renowned fishing lodge situated on the north bank of the river just a mile below Quake Lake. He was also the first person to call attention to the dam malfunction that occurred in the wee hours of the morning on Nov. 30.

McClure says that he went into the shop for a typical day of work that Tuesday morning. He was busy shipping online orders when a regular customer walked in around 9 a.m. and asked where all the water in the river had gone. McClure assumed that the Madison was running at its typical low winter flow of 600 to 650 cfs, and he told the customer as much. But when he visited the USGS website and saw the gauge registering closer to 200 cfs, he immediately left the fly shop and drove up Highway 287 to the short stretch of river between Hebgen Dam and Quake Lake.

“I went back up there just to go see for myself,” McClure says. “It was a shot to the gut when I rounded the corner and saw a spawning channel damn near dry. It was surreal.”

He says that because of its proximity to Hebgen Dam itself, the water in the “Between the Lakes” stretch dropped out immediately when the dam malfunction occurred eight to nine hours prior. This was concerning, he explains, because the relatively shallow and fast-flowing channels in this stretch contain some of the best spawning habitat for brown trout in the entire upper river. And since browns spawn in the fall, this was really the worst possible time of year for those channels to dry up.

Recognizing the gravity of the situation, McClure started making phone calls. But he was unable to reach anyone with NorthWestern Energy, the utility company that owns and operates Hebgen Dam. He then called some of his fellow guides, who grabbed waders, nets, and buckets. They started rescuing fish—browns, rainbows, cutthroat, whitefish, as well as sculpins and other forage fish—that had gotten stranded in some of the shallower side channels by scooping them into buckets and moving them into the remaining deeper pools.

By that point, Kelly Galloup—the veteran guide and influential fly-designer who owns Galloup’s Slide Inn—had gotten involved and was reaching out to some of the other fly shops and outfitters in the area.

“They all went up there and started saving fish that were stranded,” Galloup says. “It was mostly juveniles. Very few adults were stranded because they understand to follow the water when it recedes, but the juveniles don’t. And, of course, a lot of your spawning redds were exposed, so that was a problem.”

Galloup says that he and McClure eventually got in touch with Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks, and that hydro engineers with NorthWestern Energy showed up to the scene around 1 p.m.—approximately 12 hours after a critical component in the one of the dam’s spillway gates had failed. After diagnosing the problem, the engineers announced that it could take three to five days to replace the part, which, Galloup says, “created a very big panic.” Although they were having success in rescuing juvenile fish, he says, “it was the eggs everyone was worried about.”

This news launched the local river community into full-blown crisis management, and Galloup and McClure teamed up with the Madison River Foundation to send a call-out to everyone in the region.

“It became an all-hands-on-deck kind of thing,” McClure says. And although everyone returned home at nightfall after rescuing fish all afternoon, he says that “nobody really went to bed that night.”

The next morning, however, McClure and Galloup were elated to see how many people had answered the River Foundation’s call and had shown up with buckets, ready to lend a hand: There were more than 100 people ready to deploy to the upper river.

“We had guides coming from different states,” Galloup says. “They came from Idaho and Wyoming and Missoula. I even had people from California and South Dakota calling, saying they could be here in 9 to 13 hours. By the afternoon, there was something like 200 people up there, and that was all within 16 hours [of when we first recognized the problem]. It was badass.”

Fifteen of those recruits were volunteers from NorthWestern Energy, according to Jo Dee Black, the utility’s public information specialist. Black says that after they diagnosed the problem, “engineers and personnel worked around the clock to develop a repair plan and restore gate functionality and river flows as quickly as possible.”

Black explains that the utility company worked with the Anaconda Foundry Fabrication Company to fabricate and machine the new gate component. They delivered the part to Hebgen Dam Wednesday evening, and flows in the Madison were restored just before midnight on Dec. 2—roughly 48 hours after the crisis began. MFWP lifted the emergency angling closure on the river the following day.

“Folks dropped everything for the river”

“In their credit, they got it done very quickly,” Galloup says. “But hopefully this raises an alarm. And if nothing else comes from this debacle, hopefully Northwest Energy comes up with a 1-800 number.”

McClure agrees. He says that the most frustrating part of the whole situation was that a local fly shop was the first to know about it. Anybody with internet access could have recognized the sudden and sustained drop in flows, he explains. And the fact that it took so long to get an engineer on the scene only compounded his frustration.

“I try not to get too angry about it, but at the end of the day when you’re responsible for a resource as incredible as the Madison, there should be emergency procedures in place so that if something happens like this, there’s a plan and a call to action,” McClure says. “The most important thing going forward is that there should be emergency numbers for NorthWestern Energy in case something goes wrong.”

The executive director of the Madison River Foundation, John Malovich, says the nonprofit has already looked into creating some sort of public hotline or communication system in case of a river-related emergency. Malovich also points to the installation of an emergency pump at the base of Hebgen Dam as a potential solution, and he says the Foundation has already offered to buy a pump and donate it to NorthWestern Energy.

Both strategies would be a step in the right direction. But the way Malovich sees it, there’s not a phone number or a machine in the world that can take care of a river on its own. That role, he contends, falls on the stewards of the river, and he says the Madison is fortunate to have one of the most passionate groups of river advocates of any watershed in the Western United States.

“There’s not a person that’s attached to this river that doesn’t have the utmost love and passion and respect for this resource,” Malovich says. “Folks dropped everything for the river, and to me that’s the critical mass of this entire thing. The river is so important to all these people that they stopped everything they were doing to answer its call.”

Taking Stock of a Near Catastrophe

Once NorthWestern Energy diagnosed and fixed the problem, Black says, the company focused on understanding how and why the problem occurred, then establishing corrective actions that would prevent a similar failure in the future. She tells Outdoor Life that the utility company “will continue to work with MFWP to develop a plan to assess the extent of impact on the fishery. Once that impact is identified, NorthWestern Energy is committed to appropriate follow-up actions.”

Unfortunately, it will take time—perhaps up to two years—until stakeholders can fully understand the true impacts that the dam malfunction had on trout populations in the upper Madison River. That’s according to MFWP fisheries manager Travis Horton, who says he has since met with the utility company to discuss ways to implement redundancies in the safety and alarm systems, and to build resiliency into the dam.

Horton explains that the agency typically monitors trout populations in the Madison by conducting an annual sampling event, which is when fisheries biologists electroshock a specific stretch of river from a boat and count the number of fish that float to the surface. (This practice dazes the fish temporarily; they recover quickly from the shock.)

“Our typical annual monitoring is downstream of Quake Lake a few miles, and that’s a fall sampling event,” Horton says. “Typically, we don’t capture juvenile fish during that time of year, so in order to see an actual change in the number of fish, it will end up being the fall of 2023.”

Galloup, however, is staying positive, and he says the impacts on the Madison’s overall trout population could have been a lot worse.

“I don’t want to downplay it, because it could have been fucking catastrophic,” Galloup says. “But we were so successful at getting those juvenile fish out. I don’t think we lost more than 500 juveniles.”

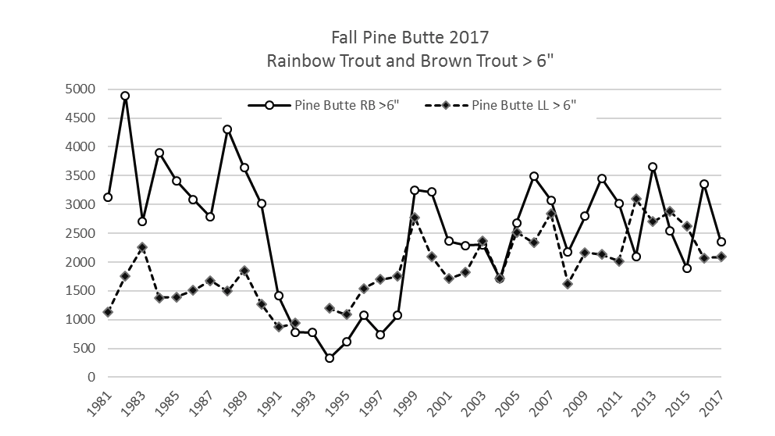

He says that losing that many fish in a short stretch of river should have a marginal effect on the overall population. Sampling events conducted by MFWP in recent years show an average of 3,000 or more trout per mile in some stretches of the Madison.

There were several factors that prevented the situation from becoming truly disastrous. For one, the weather was unseasonably warm that week and the temperature never dipped below 32°F. This kept trout eggs that were in the shallowest channels from freezing completely. It also meant that water from the tributaries downstream of Quake Lake continued to add volume to the river because those creeks, which are usually frozen by the end of November, were still flowing.

“For such a terrible situation, I really think we dodged a bullet,” McClure says, adding that the biggest factor in preventing an actual disaster was the local river community’s united response to the situation. “It just shows you how many people were willing to rally to help out a river in need. And if it happened on the Henry’s Fork, or any of the other rivers around here, I’d have been there as well.”

Dependence on a Dam

Hebgen Dam is one of roughly 12,000 major dams across the American West. It is unusual among Western dams, however, in that it does not produce hydroelectricity or provide water for irrigation.

“It’s unique in the Missouri River system because the license specifically describes the fact that Hebgen is a storage device,

” Malovich says.“You have multi-million-dollar homes and tourism and all this stuff that’s attached to Hebgen Dam and Lake, but none of that matters to the FERC license.”

FERC, or the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, is the federal entity that licenses and regulates dams. And Hebgen’s FERC license stipulates that the operator—in this case, NorthWestern Energy—is required to maintain flows of at least 150 cubic feet per second directly below the dam. It also requires the utility company to limit changes in outflow from the dam to 10 percent per day. Which means that during the dam malfunction, NorthWestern Energy remained in compliance with the first stipulation—but not the second.

NorthWestern has already filed an initial report with FERC about the incident, according to the Montana Free Press, and the regulatory agency is currently in the process of reviewing this report and determining next steps. The state will also play a role in investigating the situation, but it’s still unclear whether the Montana Department of Environmental Quality will fine or penalize the utility company for its role in the dam malfunction.

Hebgen Dam experienced another major failure in September 2008, when a hole in the dam’s underwater intake tower created a 400 percent increase in flows from the dam’s outlet. NorthWestern Energy spent the next nine years fixing the problem, and in the process, they rebuilt and replaced the spillway gates. And from Galloup’s perspective, this is one of the most disturbing aspects of the more recent dam debacle.

“It’s just frightening to me because this is a 3- or 4-year-old dam on one of the most historic rivers in the world,” Galloup says. “If it was 80 years old, I’d say okay. But it’s not.”

So why should we keep fixing it? Because Hebgen Dam is absolutely critical to the health of the blue-ribbon fishery that the Madison River supports. By pulling water from the bottom of Hebgen, it provides a constant supply of cold, oxygenated water—a resource that is in increasingly short supply across a warming, drought-stricken West.

The importance of Hebgen Dam became even clearer this summer, when low flows and warming temperatures led to widespread closures and angling restrictions across the state of Montana.

“This last summer,” Horton explains, “we had more rivers closed and more hoot owls than ever before in history because of how poor the water year was.”

Horton explains that over the course of this summer, nearly every river in the southwestern part of the state—including the Big Hole, the Yellowstone, and the Missouri—was either closed entirely or placed on hoot owl restrictions, which prohibit fishing from 2 p.m. until midnight when specific temperature or flow thresholds are reached. And while the upper Madison River (above Ennis Lake) never got above 69°F, MFWP still decided to place the upper river under hoot owl restrictions late in the season due to the agency’s fears of what it calls “angler displacement.”

Read Next: The Future of Trout Fishing in the West Could Be in Hot Water

“Flows and temperatures were not bad on the Madison River,” Horton says. “They were actually some of the best in the state just because of the operation of Hebgen Dam. But the concern was having throngs of people coming from everywhere else that was closed or restricted.”

So, whether we like it or not, the health of the Madison River fishery is now dependent on Hebgen Dam. Fortunately for the river, it has plenty of watchful eyes and dedicated stewards that will do their best to ensure that the next debacle doesn’t turn into a disaster.