When you’ve been lost in an unfamiliar part of town, I’ll bet you turned the sound down on the radio so you could “see better”.

Joking aside, being lost is not funny. It unbalances our center, sending us into heightened awareness.

Walking around a corner and seeing a familiar building across the way lifts that sinking feeling. Your feel-good endorphins kick in, and confidence returns as you take control of your situation.

Navigation is so part of our world that we don’t even recognize it anymore. We take it for granted until we are out of our comfort zone.

I’m not saying you should carry a compass around town; we have phones that do that for us already.

You have, however, traveled out of town, been without cell reception or you just want to head into the wilds to recharge your mind.

Old-school navigation is an absolute necessity for obvious reasons: if you can navigate you can find your way back.

Hitting the backwoods of Virginia with some of my Navy SEAL buddies certainly made this point clear to me. I was in another country, in a different hemisphere, in unfamiliar territory.

Once off the main road, everything changes, and it’s very easy to become disorientated…

Years of training came flooding to the surface and had me reaching for the comfort of my trusty compass, much to my buddies’ amusement and nods of respect.

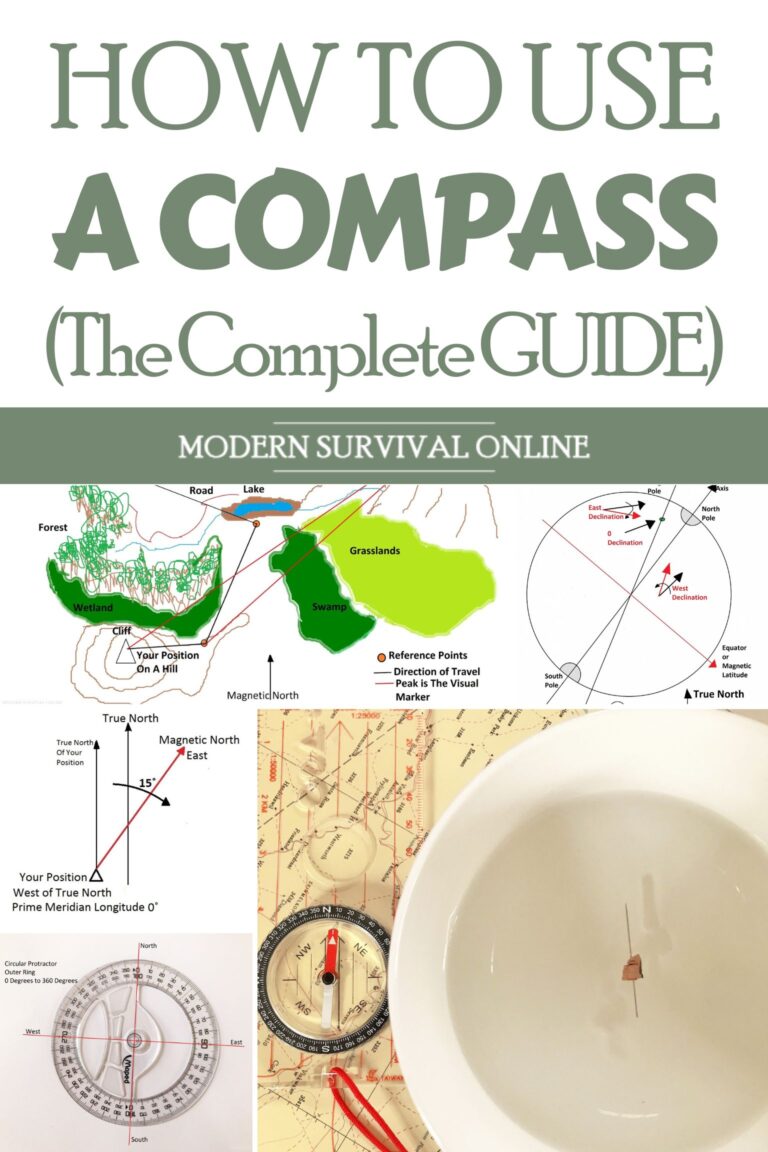

In this article, I will take you through the basics of compass work, and help you understand the groundwork and how to apply your knowledge.

You will upskill, taking your confidence to a new level, just don’t get overconfident. Right, let’s get started.

A Brief History of the Compass

The compass is arguably the most important innovation in navigation equipment in the history of mankind. It predates the sextant by thousands of years, which is the one instrument that has been used to open up the world to exploration, discovery, and human expansion.

The history of the compass is firmly rooted in construction and land ownership. The need for accurate land surveying is the sole motivation for its invention.

Positioning out plots of land for agricultural use, town planning, and infrastructure development — all provided the platform for the emergence of the compass.

The earliest recorded use of a compass-type device is out of China during the Quin dynasty (221-206 BC).

A lodestone, magnetite is a naturally magnetized mineral element, used to establish true South aiding early soothsayers and fortune tellers with their conjuring and predictions.

It wasn’t long before the directional qualities were recognized and put to better use…

More importantly, these loadstones, or “South Pointers”, were used to orientate building construction and infrastructure development.

The first compasses showing the four cardinal points emerged somewhere in the late second century BC during the Han Dynasty.

Barbara M. Kreutz in her book, Mediterranean Contributions to the Medieval Mariner’s Compass, sheds light on the compass’s historical development.

With ongoing use, the compass formally saw use with the Chinese military for land navigation and maritime navigation from the early part of the 11th century.

The base was made of brass and the spoon-shaped lodestone was placed in the middle which, when given a little spin, would come to a stop and orientate on the North-South axis.

Further investigation found that metal needles that were rubbed on the loadstone became magnetized, and when placed in a light cork floating in water would also orientate on the North-South cardinal points, a wet compass.

It was found that the same needle if suspended from a thin silk thread would also orientate on the North-South axis.

The importance of this discovery is that the compass became portable, and land and maritime navigation had entered a new age of accurate navigation.

As trade with the Middle East opened up, the knowledge of the compass spread into Europe where it was combined with ongoing European developments…

The Compass Rose

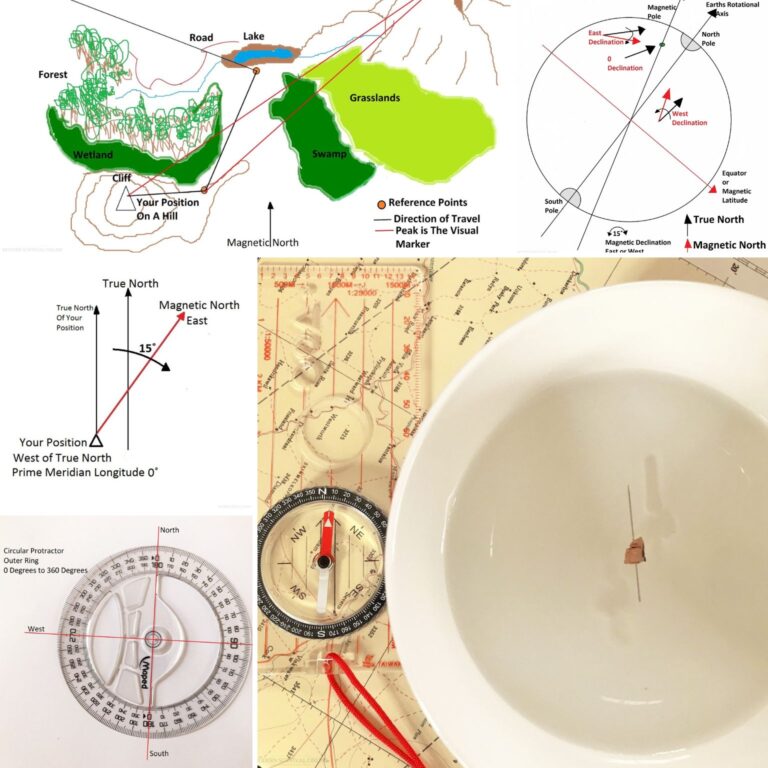

The Compass Rose is an old-school Compass Card. It can be placed on or drawn onto a flat surface and used with a basic compass to identify the cardinal and the ordinal points of the compass.

The eight points on the card can be abbreviated into North (N) South (S) East (E) West (W), the Cardinal Points, and North East (NE) North West (NW) South East (SE) South West (SW).

In maritime terms, these are:

- The four-point compass rose card represents the basic winds, or the North, South, East, and West cardinal points. These are at 90 degree angles to each other.

- The eight-point compass rose card represents the eight principal winds of the North East, North West, South East, and South West. The eight points are at 45 degrees from each other.

- The angles can be further divided into halves all the way down to the smallest points of degrees. This will help you to refine direction if you are using an emergency compass.

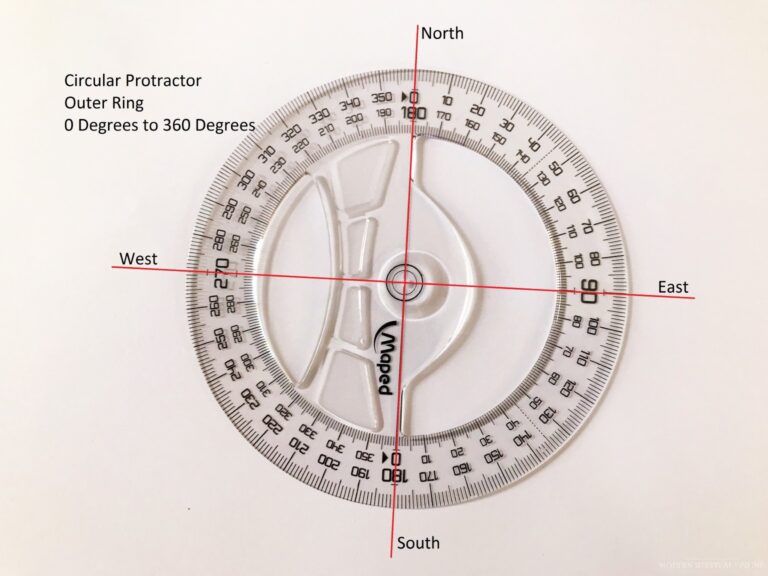

- Drawing a circle around the center of the compass rose will lay out a 360 degrees dial with 10 degrees intervals like a modern circular protractor. These can be refined further by dividing the space between the 10-degree intervals, by 10 degrees of 1.

The Modern Compass

There are four distinct variations of the compass for land navigation:

- The Baseplate Liquid Compass where the housing for the compass needle is filled with liquid to give the pointer more stability. It is the cheapest and offers excellent value for money. It is suitable for plotting as the baseplate has integrated scales and offers substantial navigational qualities.

- The Mirror Compass is the Baseplate Compass fitted with a flip-top mirror housing with a sight line to aid in accurately determining the bearing of a landmark.

- The Lensatic Compass offers a heightened degree of pressure using a mirrored base and peeps sight alignment system. This allows the user to sight the compass on a land feature while taking measured degree readings.

- It has a cousin called the Prismatic Compass, with similar features, and uses a prism peep sighting system, offering a finer degree of accuracy. This compass is also called the Military Prismatic Compass.

As a military operator, I cut my teeth on the military issue Prismatic compass, which used Mils instead of degrees. It’s very accurate but complex unless used extensively and practiced regularly.

There are 6400 mils in 360 degrees, giving a degree of accuracy not attainable with a compass marked only in degrees.

The baseplate and lensatic compasses are my go-to, with the baseplate being the most suitable for ease of use.

In this article we will focus on the baseplate compass; its ease of use combined with functionality make it the first choice when starting out.

It’s important to get in as much practical use as possible, refine your skill set and develop a natural sense of direction.

The Baseplate Mounted Compass

The compass is a relatively simple instrument to use. The magnetic needle always points to the magnetic North, making the compass orientation simple and referencing easy.

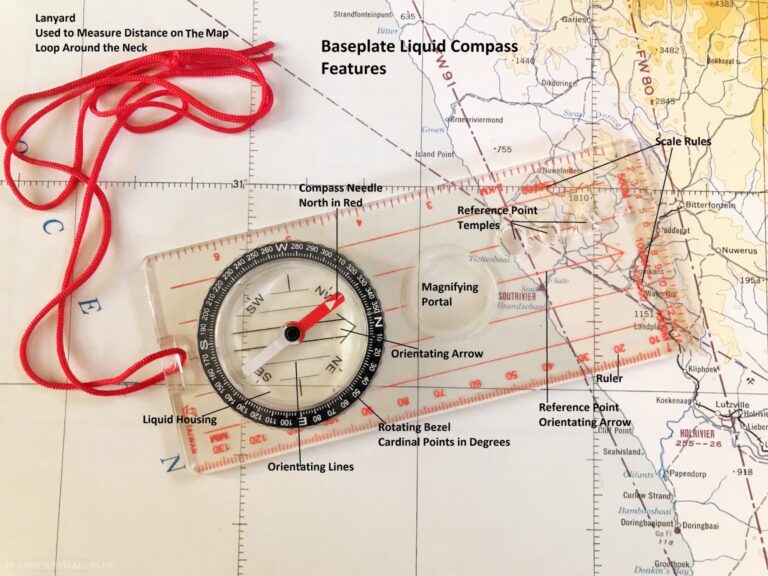

Know your tools, and they will serve you well:

- Red Magnetic Needle

- North Orientating Arrow

- Liquid Housing

- Rotating Bezel in Degrees

- Scale Rues in 1:25000 and 1:50000

- Map Reading Magnifying Glass

- Reference Point Map Stencil Plotting Template

- Ruler in millimeters for plotting a course and distance

- Reference Point Orientation Arrow or The Direction of Travel Arrow

- A lanyard is used to secure the compass around the neck. It can also be used to measure route distance on a map.

- Reference Point Stencil Templates – to draw directly onto the map

Here’s How It Works

The red end of the needle always points North, Magnetic North. Setting the rotating bezel to match the orientating arrow will line up your compass with the travel arrow.

Rotate the base plate until the compass needle seats in the orientating arrow outline or frame. This is called boxing the needle or “Red in The Shed”.

This is important when we calculate true North making allowances for Magnetic Declination.

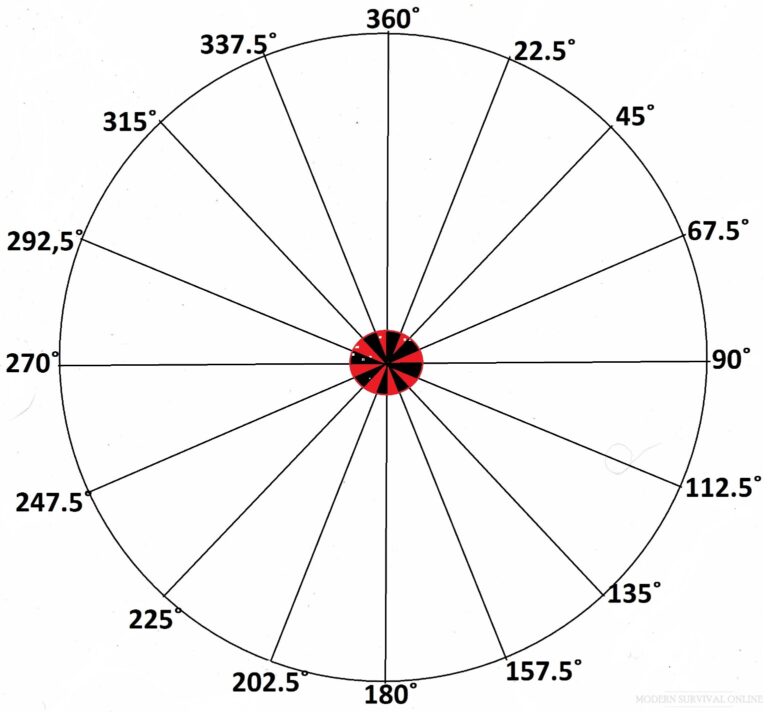

The Rotating Bezel is graduated clockwise from 0˚ to 360˚. Each degree East or West allows the user to find the bearing of a Reference Point if the coordinates are known.

A bearing then is the reference point relative to your position, given in degrees. The coordinates need to account for the difference between Magnetic North and True North.

If you know the coordinates, the bezel is rotated until the bearing is in line with the Travel Direction Arrow also called shooting a bearing. This is the bearing relative to True North or Magnetic North.

The Compass Needle is Boxed in the Orientation Arrow. This is also referred to as “Red in The Shed”:

- The Red Arrow Line leading off North is the Direction of Travel Arrow

- Box the red Compass Needle in the Orientation Arrow

- Dial The Bezel to Box the Compass Needle

- The Degree In Line with the Travel Arrow is The Directional Bearing

Ensure that you are taking your readings away from metal objects, magnets, radios, other compasses, overhead power lines, and electrical equipment.

These will all interfere with the needle’s alignment as magnetic or electromagnetic fields surrounding them.

Magnetic Declination

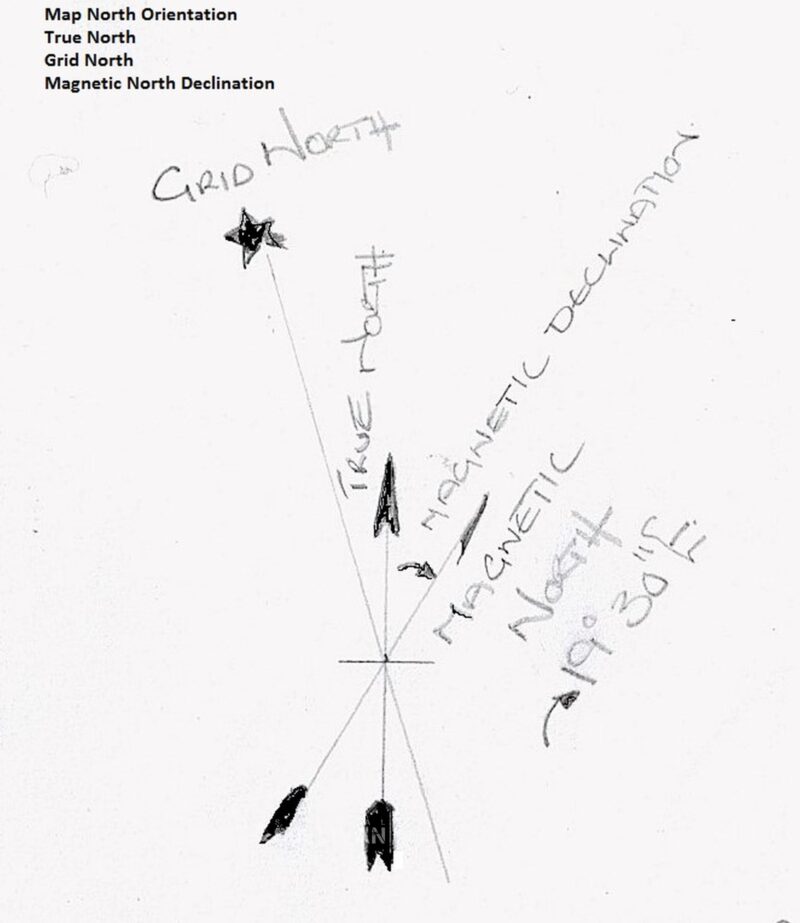

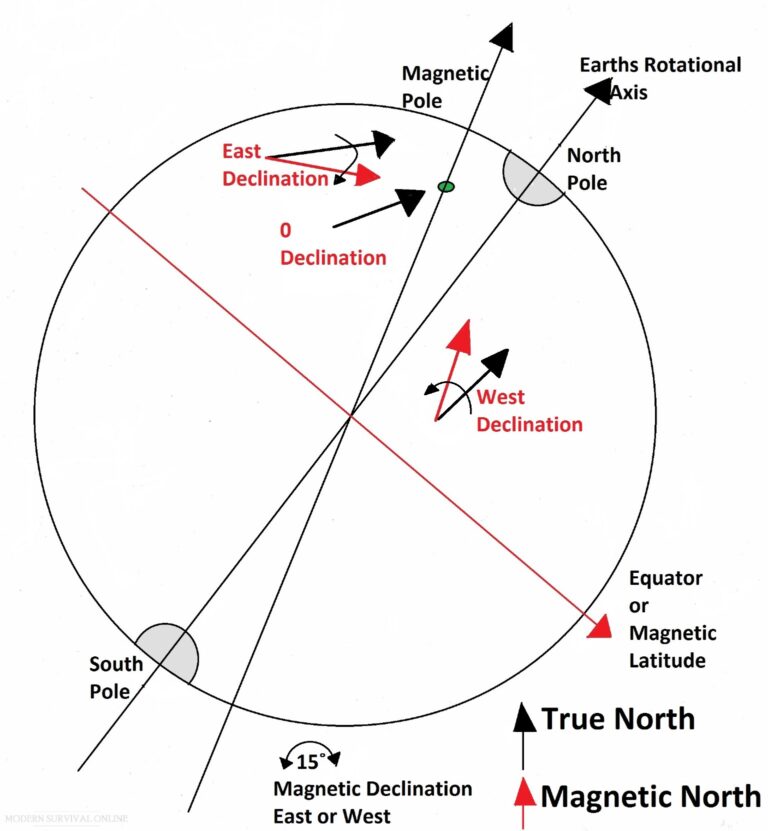

The difference in the angle between Magnetic Declination and True North is a vital calculation to determine your correct heading. Even a few degrees off will multiply into a huge angle of error taking you off course.

When using a compass on its own, the direction is given as Magnetic North globe showing True North and Magnetic North.

- When True North and Magnetic North are aligned, declination is 0˚.

- East of True North, the magnetized compass needle indicates a Westerly Magnetic declination or East = West

- West of True North the magnetized compass needle indicates an Easterly Magnetic declination.

- The angle of Magnetic Declination is added for East Declination

- The angle of Magnetic Declination is added to 0˚ for the West Declination and subtracted from the East Declination.

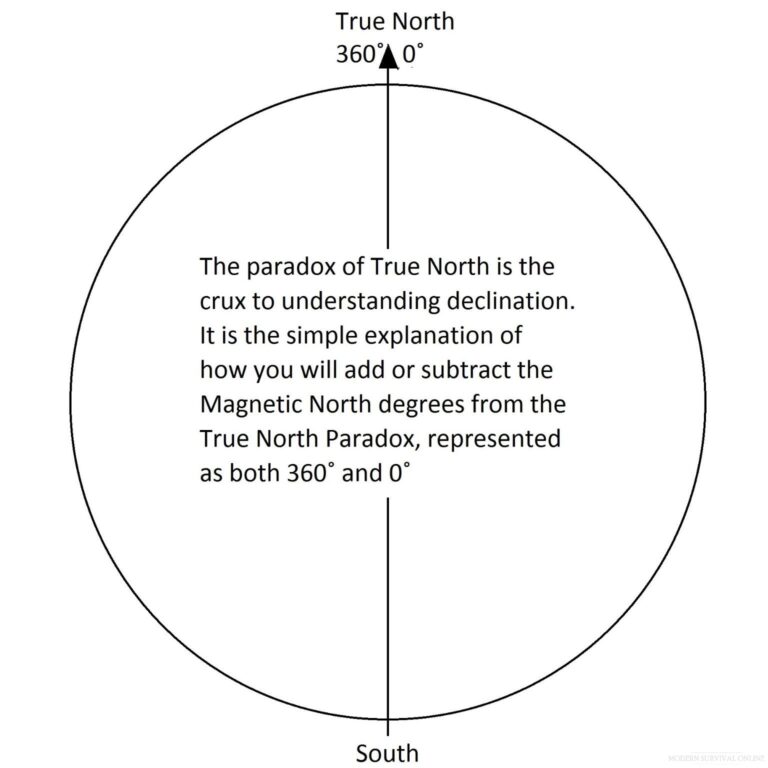

The True North Paradox

Knowing when to add or subtract Magnetic North from True North is a regular question that comes up in training.

Any mistake will take you so far off course that you could seriously jeopardize your chances of survival.

Consider this, your compass dial is graduated in degrees and increases clockwise moving from 0˚ to 360˚.

True North is Both 0˚ and 360˚.

This single piece of obvious information will uplift your understanding of declination, demystifying it.

True North 0˚ is the Prime Meridian, given as the line of longitude running through Greenwich.

In truth, all lines of longitude are 0˚ or 360˚. The lines of longitude are imaginary lines. We have to start somewhere that circumnavigates the earth which all converge on and cross over the poles.

For our purposes to understand our world we have named the longitudinal lines 0˚ to 360˚ degrees running clockwise around the world beginning in Greenwich.

Your position relative to the prime meridian will give you, your magnetic declination.

The prime meridian creates the Eastern and Western hemispheres, and is responsible for the date lines which we use to further understand the sun’s cycles around the earth’s rotation, night and day, and fathom lines of longitude.

Application of the Paradox

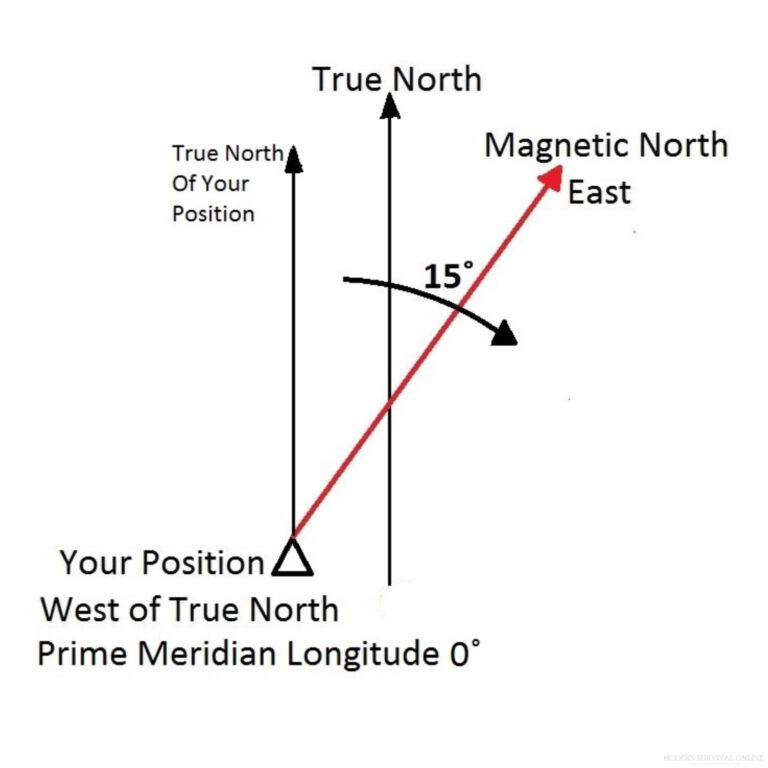

West is Best

- Your position is West of True North = Declination is East of your position

- Referring to the diagram. Placing your compass on the True North Line at 0, the Compass Needle will show 15˚ East of True North

- Rotating the bezel dial 15˚ clockwise to the 15˚ mark will orientate your compass to the True North Direction.

- This will be bearing 345˚

- You have subtracted 15˚ from 360˚

- West is Best

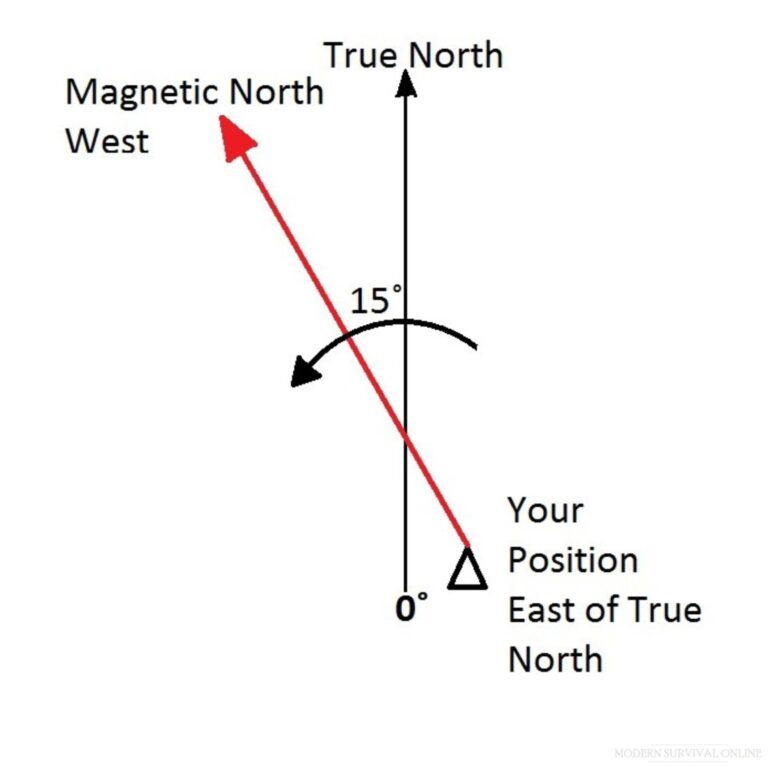

East is Least

- Your position is East of True North = Declination is East of your position

- Referring to the diagram. Placing your compass on the True North Line, the Compass Needle will show 15˚ East of True North

- Rotating the bezel dial 15˚ clockwise to the 15˚ mark will orientate your compass to the True North Direction.

- This will be bearing 15˚

- You have added 15˚ to 0˚

- East is Least

Before heading out into the unknown it will serve you well to familiarize yourself with the declination of the area you intend to visit. Magnetic Declination can be tracked worldwide online.

Depending on where you find yourself the angle of error can vary from 2˚ or 3˚ to 20˚ plus degrees. This can mean missing your Reference Point by meters or miles.

Working with Declination

Working with declination should be simpler now and make much more sense. Magnetic declination changes on a yearly basis which shifts with the earth’s geological movement.

The Sun’s intensity has a direct influence on the Earth’s Magnetic field which also influences delineation.

Declination will vary depending on your position in relation to the North Pole or True North. Be sure to keep up to date with the degrees of change on a regular basis here on the web.

Declination can be applied in two ways:

- Declination as given by a map that is up to date.

- Declination is known, it’s a given for a specific area.

Map Work

Modern Topographic maps have the magnetic declination for the specific area printed on them. This will help you to orientate your compass to True North and your topographic map.

The top of the map is always North. Once you have determined True North you can orientate your map to the ground and everything you see on the map will be orientated to the ground.

Shooting a bearing with your compass will allow you to plot your direction from your position relative to the area you are in.

We will explore this further in the article Map and Compass work.

What Happens When You Have No Map or Declination?

The isographic map is a detailed world map of magnetic declination. It can be downloaded and printed to accompany you on your journey.

From your position, align the orientation arrow of your compass with the travel direction arrow. Hold the compass out in front of you, and the magnetic needle will align with the magnetic north.

Shifting your body around until the needle is boxed or Red in The Shed, will give you the magnetic bearing.

Your position is west of the prime meridian, True North will be to your left. You will have to be familiar with landmarks and features that are True north indicators, use the sun or the stars to determine true north to verify your findings.

Once established, you can shoot a bearing in the direction you wish to travel, and be confident that you are on course.

Working With Magnetic North

If working only with Magnetic North, you will shoot a bearing in the direction you wish to travel, and stay on the bearing to the point of reference. As you navigate between points, you will keep using Magnetic North as your reference.

You can triangulate your position using three known or identifiable points. Even if you are in unfamiliar territory, this will help you establish your position on the ground.

Generally, people get lost in familiar surroundings with a known starting point and landmarks.

Keeping your head about you, remaining calm, and reverting to your compass work will help you orientate yourself to the environment and find your way back to the beginning.

Terrain Assessment, and Pathfinding

The first two terms are associated with map work, where the map and ground are orientated to correspond with each other, allowing you to position yourself.

You are however stranded without a map, so build one. Even a basic drawing based on what you can see will give you control of your surroundings and provide meaning to the environment.

Pathfinding is a natural form of navigation used for millennia, the real talent is in choosing the right path, here is where Terrain Assessment and Association come into play.

More specifically:

- What do you see?

- How will the environment impact your movement?

- How will you get there?

- Where are you going?

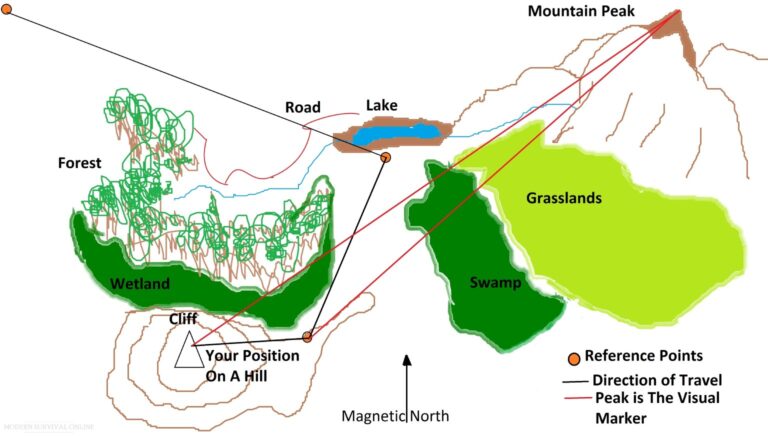

Known Position

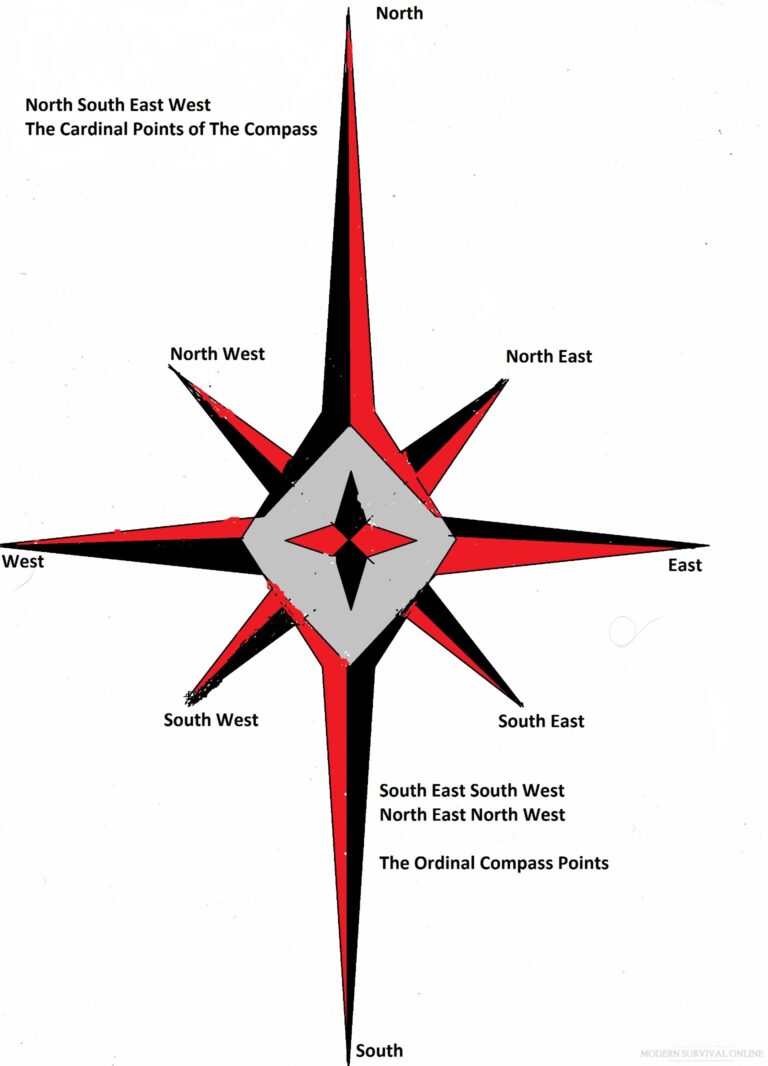

Your position on the hill gives you a view of the surroundings, allowing you to assess the way out. Taking a look at the map you can see that the lake in the distance is what you want to head for.

The road is clearly visible as a defined line in the distance but getting there will present a problem.

Terrain Assessment

The cliffside in the diagram above has blocked out a part of the route down. The wetland may not be viable as you can get bogged down. The same goes for the swamp area.

The direct route is not always the safest or fastest route, taking a little time to ensure you assess the terrain will save you many hours of trudging.

Pathfinding

This is called pathfinding. As the name implies, you will plot your course out of the wilderness using the landmarks and features available to you, crossing the best terrain possible.

Terrain assessment is vital in plotting your route; ending up in the swamp would not be ideal.

Here, your compass will assist you, and declination will have no impact on your planning.

Baseline

In the distance you can see the lake, this is the point you want to head for, it’s large and prominent. It makes for a great reference point to head for, also called a baseline.

You can see that once you descend from the hill you are on, the lake will not be in sight anymore, your trusty compass however will help you stay on course.

Even if you are a few degrees off due to navigation errors and obstacles forcing course changes, your Baseline is still large enough that you will find it.

Aiming Off

This is also referred to as Aiming Off at times, meaning that you aim big, and miss small.

Try not to aim for small baselines if you miss them, you can waste valuable time searching for them.

The mental stress and anguish that accompanies the anguish of missing the reference point will drag at you and can seriously undermine your chances of survival.

Once you reach the lake you can follow the edge until you reach the river with the road running near it.

Handrail

The lake now becomes your guide to your next baseline called the handrail. You’ll rely on this handrail, using it to stay on course, and uplift your spirits with a sense of achievement and the knowledge that you will survive.

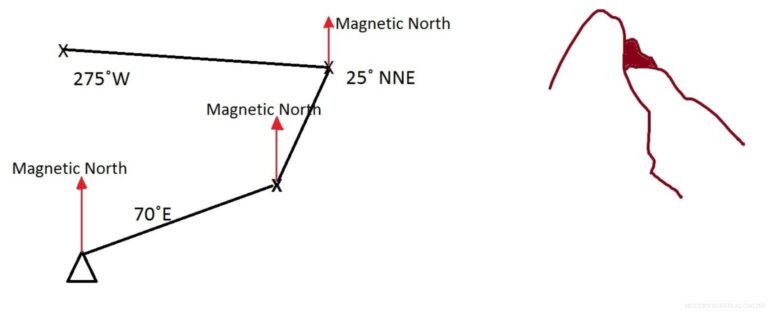

Plot Your Path

From your position, you can see the mountain peak, and shoot a bearing to the Peak. This Mountain Peak will be visible no matter where you are as you make your way to the lake. It will help you orientate yourself and maintain your bearings.

The next step is to plot your course along the path you have chosen. Pathfinding takes all the terrain features into account and gives up reference points that you will use to plot your course.

Shoot a bearing to a feature that you can see on your path; make a note of it.

Once you get to it, you’ll be able to look back at the position that you departed from and orientate yourself to the next reference point on your map.

Now shoot a bearing to your next reference point. The peak will make sure you are on track, by shooting a bearing to it from your new position and centering it for the next leg of your journey.

Set your Orientation Arrow to Magnetic North Bearing and the travel arrow to your reference point, you can check your position as you descend to the first reference point and keep on track.

Your first reference point will now be your new position and repeat the process to be off on the next leg of your route to the lake baseline. Write it down if you can…

The aim is not to stay on a True North course, but to stay on a true reference point course. You want to reach your objective and from there make your way out of the wilderness.

Not every road will take you home, but it will take you to a destination from which you can make your way home.

Safe Bearing

If, when you reach your first reference point or baseline and find that you cannot travel as planned due to an unseen obstacle you can retrace your steps along the safe path you traveled along earlier.

This is literally reversing the bearing from 70˚ E to 140˚ W, also called a back bearing, to return on your safe bearing.

The importance of drawing even a simple map becomes relevant when a heavy fog or cloud cover denies you visibility.

If, along the route you planned, you have to traverse thick undergrowth or high reeds, how will you find your way to the next reference point if you cannot see it?

Having drawn the features of the areas, or mapped them out, and taken bearings to place them in position relative to your position will provide you with the confidence to move even when visibility is poor.

This will require a different skill set to be applied.

Dead Reckoning

Dead reckoning must be the oldest form of planned navigation, it’s literally a matter of heading off in a direction for an estimated distance for a measured timed period.

Walking North towards a hill for two kilometers at 4 miles an hour will mean you are 2 miles from your previous position on a northerly bearing in half an hour.

There are three parts to Dead Reckoning:

- Direction

- Distance

- Time

Your map and compass come in useful at this point.

You have worked out your direction from your position, you have an idea of the speed you can travel and you can work out the time taken to travel.

If you have all three then you’re on track, if you only have two then you can work out the third.

Dead reckoning is a tried and tested maritime navigational method that can be applied to land navigation.

Dead reckoning always starts with a known point. This can be confusing if you are lost, right?

Not so… You may not know the exact grid reference of the point of the earth you are standing on but you know where you are right now. This is your known starting point.

You are navigating out of the wilderness and using Dead Reckoning to find your way from one point to another, giving you powerful insights into how you will be able to predict your future movement.

Direction

Your compass is the starting point, irrespective of where you are it will point to Magnetic North. Shoot a bearing to a reference point you want to head to; this is your direction.

Distance

Count your paces to this point. Depending on the length of your stride, 60 to 70 right-only or left-only paces will equal 100 meters. Now you have a rough estimate of how far you have traveled.

Speed

Time yourself to this point using your watch. Apply the factor of 3.6, for converting meters per second into kilometers per hour, this is seconds x the factor 3.6.

1m/s x 3.6 = 3.6 kilometers per hour

Time yourself between two points of a given distance. Even if you have to pace it out and then time yourself, this will assist you in calculating YOUR average speed.

Calculating Your Options

Using your watch, you can determine the time taken to move between two points.

Dead Reckoning gives up a formula to determine Speed, Distance, and Time.

Speed = Distance ÷ Time

S = D ÷ T

There are three different ways to use this formula:

- distance ÷ time = speed, example: 3.8 miles ÷ 1.3 hours = 2.9 miles per hour

- speed × time = distance, example: 2.9 mph x 1.3 hours = 3.8 miles

- distance ÷ speed = time, example: 3.8 miles ÷ 2.9 mph = 1.3 hours

Trained athletes can run 100 meters in 15 seconds or better, which means that the athlete is running at:

100 meters (D) ÷ 15 seconds (T) = 6.6 meters per second (S) (that’s right, 6.6 meters in 1 second)

Using the factor 3.6 for converting m/s into k/h:

6.6m/s x 3.6 = 24 kilometers an hour (almost 15 miles per hour)

Not many of us can keep up this kind of pace or even one vaguely resembling 15 mph for any length of time.

You have to determine your walking pace, a good brisk walking pace, to eat up the distance while conserving energy and water is 4.8 kilometers per hour (km/h) or 3 miles per hour (mph).

Your backpack or any amount of water you carry will impact your speed.

If you have a party with you, you will be subject to the slowest members’ pace or risk losing them. This is a big contributor to those getting lost.

Taking a Look at the Math

Average Speed: 1.35 m/s

Distance: 100 meters

100 meters ÷1.35 seconds = 74 seconds

To walk 100 meters =74 seconds

1.23 minutes/100meters, 12.33 minutes to travel 1 kilometer

Kilometers per hour

60 minutes ÷12.33 minutes = 4.86 kilometers/ hour

Miles Per Hour

1.6 kph to 1 mph

4.86 kph ÷ 1.6kph = 3mph

Your watch got lost, your cell phone battery is flat and you have no reliable way of keeping time, can you manage? The answer is YES!

Without the benefit of a watch, we can work at an average walking pace of 1.35 meters per second. A study conducted measured the gait or stride of test subjects to ascertain an average per age.

Taking these figures, we can conservatively extrapolate an average for men and women across the age spectrum, that one walking pace distance is approximately 1 meter, and that distance is covered in 1.35 meters per second.

Using the pace count, an average of 60 to 70 paces (100 meters) is equal to 81 seconds.

Plotting your course, estimating your time to travel this course, and working out the actual time you traveled are now all within reach using this simple formula and your compass.

If your calculations for distance are out you will walk further and longer or vice versa.

This holds for your walking speed, which is affected by natural factors or fatigue or injury, may be slower or faster, changing your time value, making arrival sooner or later.

Dead reckoning is not a precise art, it’s flawed and vulnerable to geographic features, gradient, and ground quality. Weather and wind can foul your progress.

Your age and physical condition each play vital roles in determining your speed and influence the quality of your calculations.

That said, dead reckoning is better than having no plan. It got the Vikings across the ocean to the British Isles and beyond, even as far as the Americas.

Christopher Columbus navigated across the open Atlantic to the shores of America and back again to Spain using Dead Reckoning.

It may not be the most accurate yet it will give you the confidence to make a move, save yourself from circumstances and head out to discover the path home.

Working with distances and times that are not exact is, of course, problematic and open to error. Error is compounded by distance traveled, called the angle of error.

Your compass will give you control of your direction, it can take longer or could be further, but you are in control and have rough estimates to work with.

Keep a Notebook

Keep a log, and use a notebook to jot down your work. Compass work is like learning another language, writing down your findings and checking your results will strengthen your skills.

You have to use your equipment, get out in nature and explore, take routes you know well, and plot their course.

Walk the course, and compare your notes. Join a local hiking group, and mingle with experienced field guides.

If ask for help and assistance, almost all will oblige. Many take pleasure in assisting new members to learn the necessary skills.

Wrap-Up

In this article, I have focused on using a baseplate compass without a declination setting. The aim is to introduce the easiest compass to use that will fulfill your navigational needs.

Once you have a firm foundation using the baseplate compass, you should move on to the mirror compass.

For highly detailed and accurate work, there is none other than the Mils compass., which requires detailed mathematical calculations and conversions.

Everything becomes easier with use and practice. Do not be daunted, everyone can do it.

Like what you read?

Like what you read?

Then you’re gonna love my free PDF, 20 common survival items, 20 uncommon survival uses for each. That’s 400 total uses for these dirt-cheap little items!

Just enter your primary e-mail below to get your link:

We will not spam you.