This article was originally published by G. Keith Smith, MD at The Mises Institute.

While the Free Market Medical Association [FMMA] is made up of buyers, sellers, and intermediaries, we decided this year to focus primarily on buyers. That decision inspired the remarks I’ll make today. We have always believed that the growth of this movement hinged on an empowered, enlightened, and red-pilled buyer. The seller’s then forced to accommodate buyer preferences.

In spite of the claims of the woke Left, a failure of the free market is not to blame for the disaster known as the American healthcare system. It is precisely the opposite. The disastrous part is thanks to the government intervention and interference that has prevented the market from working its magic. The absence of an unfettered market is to blame. How do we know this? We know this because in every other industry, a free market leads to higher quality and lower prices. We know this because once upon a time, not that long ago, affordable high-quality care was the rule, at least until big government entered the scene. We also know this because the movement started by this organization has spread, and everywhere it goes, it brings higher quality and lower prices.

But what exactly does it mean to say market discipline is absent? To answer this question is the key, I believe, to discovering the path to the high quality and affordability that only a free market can provide.

In short, market discipline is weak or absent to the extent that the buyer has been placed at a disadvantage. Government is to blame for the weakened bargaining position of the buyer, as the predatory state’s primary business is to sell favors to the sellers. Indeed, the government at all levels has been busy selling favors to industry big shots, and every favor sold weakens the influence and choices the buyer has in the marketplace. This is why Dr. Per Bylund refers to government regulations as choice restrictions. While this all sounds like common sense, I think a granular look at the buyer-seller relationship will yield some useful insights, particularly the importance of the buyer’s role and the hazard of placing too much importance on the seller’s role in this industry.

What did Ludwig von Mises have to say about the role of the buyer in an exchange? In his brilliant 1944 book titled Bureaucracy, he said:

The capitalists, the enterprisers, and the farmers are instrumental in the conduct of economic affairs. They are at the helm and steer the ship. But they are not free to shape its course. They are not supreme, they are steersmen only, bound to obey unconditionally the captain’s orders. The captain is the consumer.

The real bosses [under capitalism] are the consumers. They, by their buying and by their abstention from buying, decide who should own the capital and run the plants. They determine what should be produced and in what quantity and quality. Their attitudes result either in profit or in loss for the enterpriser. They make poor men rich and rich men poor. They are no easy bosses. They are full of whims and fancies, changeable and unpredictable. They do not care a whit for past merit. As soon as something is offered to them that they like better or is cheaper, they desert their old purveyors.

This, of course, is what the cartel has worked so hard to change. Without question, hospitals and their industry pals have bribed legislators and bureaucrats to avoid the same competitive market discipline that made the economic miracle of this country the envy of the world. For this reason, we must always focus on the consumer’s interests and completely discount any poor-mouthing claims of the sellers, claims which give cover to the dysfunctional arrangement we now endure.

Let’s go back even further, to the nineteenth century, when French economic Frédéric Bastiat penned his famous satirical essay “The Candlemakers’ Petition” in 1845. Here’s what he had to say about giving the seller the advantage over the buyer:

We are suffering from the intolerable competition of a foreign rival, placed, it would seem, in a condition so far superior to ours for the production of light that he absolutely inundates our national market with it at a price fabulously reduced. The moment he shows himself, our trade leaves us—all consumers apply to him; and a branch of native industry, having countless ramifications, is all at once rendered completely stagnant. This rival, who is none other than the sun, wages war mercilessly against us….

What we pray for is that it may please you to pass a law ordering the shutting up of all windows, skylights, dormer-windows, outside and inside shutters, curtains, blinds, bull’s-eyes; in a word, of all openings, holes, chinks, clefts, and fissures, by or through which the light of the sun has been in use to enter houses, to the prejudice of the meritorious manufactures with which we flatter ourselves that we have accommodated our country—a country that, in gratitude, ought not to abandon us now to a strife so unequal.

Mises and Bastiat knew full well what would happen if the buyer was placed at a disadvantage, whatever excuse the sellers or producers used.

Before I continue, we should distinguish between mutually beneficial exchange and a zero-sum, or leveraged, exchange. Always remember that the buyer and seller never voluntarily come together to exchange unless it is to the advantage of both. The seller of the milk values three dollars more than his milk, and the buyer values the milk more than his three dollars. Both parties emerge from the transaction improved from their prior position. A zero-sum exchange, in contrast, is where one party wins at the other’s expense. In this type of exchange, the buyer or the seller is victimized by the other party. This is the business model of government, and this is the business model of the medical cronies government enables. Think predator and prey. Think of yourself as clean sheets and the cronies as Amber Heard.

While there are two methods of exchange, there are two types of buyers: legitimate and illegitimate. A legitimate buyer respects mutually beneficial exchange and is represented by individual patients and any others who work as a good-faith proxy on an individual’s behalf, whether a self-funded plan or a cost-sharing ministry. Government and traditional insurance companies are illegitimate, zero-sum buyers, whose hit-and-run model is based on leveraged exchange and whose interests are diametrically opposed to the interests of patients. Patient and consumer misery are consistent with their goals. Government buyers in countries with universal care plans take this to the extreme with coerced euthanasia plans, as a citizen’s death helps their balance sheet. Doctors in Great Britain are actually paid a bounty for any sick or elderly patients they can lead to the euthanasia slaughterhouse.

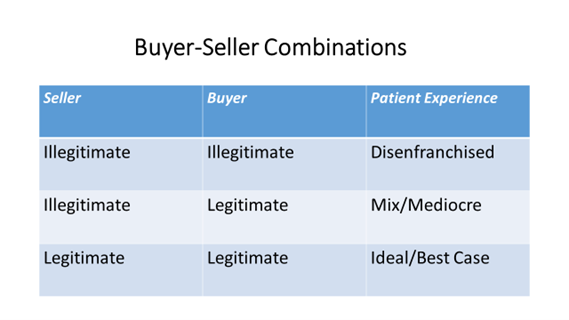

There are also two types of sellers: those who seek to maximize revenue and those who seek to maximize delivery of value. The resulting combinations of these buyer and seller types can result in one or even both parties, buyer and seller, acting in bad faith. Think pure bad faith when a hospital owns an insurance company. Think pure bad faith with an accountable care organization model, where a hospital basically owns an HMO. The patient is completely disenfranchised, vulnerable, and without an advocate, as both the buyer and the seller are illegitimate. Things are a little better for the patient when only one of the parties to the exchange is illegitimate—say, when a legitimate cost-sharing ministry or the self-funded employer buys from a price-gouging hospital. The patient experience is maximized when both parties are legitimate and seek mutual benefit. In this instance of symbiotic legitimacy, the provision of a substandard service invites the merciless market forces that will put one out of business. The quality question is therefore solved when both buyer and seller are legitimate. Quality is “baked in,” as FMMA cofounder Jay Kempton says.

When the government places consumers at a disadvantage, prices soar and quality plummets. This is clear in any market where hospital consolidation has taken place. It became crystal clear when the number of insurance companies was intentionally downsized by the Unaffordable Care Act’s medical loss ratio. The before- and after-Obamacare stock price of UnitedHealthcare makes the point that when consumer choice is limited, prices soar. When the government places sellers like hospitals or physicians at a disadvantage, with price controls or a heavy regulatory burden, shortages materialize and quality plummets. Burdensome regulations are crafted by industry participants large enough to survive—and as smaller sellers surrender, the ensuing consolidation that leads to higher prices results. The result of all this: government can more easily sell disadvantaged consumers than disadvantaged sellers because the sellers are more willing to spend big money for advantages that can make them rich. The one thing the cronies fear is an equal playing field, the real competition of the free market. This is the core goal of the crony cartel, escaping real competition and ensuring that the seller always has the advantage. Don’t be fooled when a big insurance company and a big hospital system provide a theatrical display where one agrees to play the victim to the other, hoping people will pick sides. This is an important part of ensuring the scam stays alive, as this theatrical distraction provides an important decoy for the real play, one where the hospital and the carrier work side by side.

It hasn’t always been this way. I was fortunate during my premed years to shadow two great and extremely busy surgeons, Dr. Don Garrett and Dr. Richard Allgood. There were two hospitals in town, neither one of which could survive without these two. Drs. Garrett and Allgood never hesitated to move patients from one hospital to the other if one hospital failed to provide what the patients needed. These hospitals had to compete with each other for their referrals, and failure to do so meant disaster for them. The hospitals were accountable to all the referring physicians, essentially the proxy buyers for their patients. I should point out that the better the physician’s reputation, the busier they were, and therefore the hospital that couldn’t cater to the great doctors was punished even more severely, a quality control measure largely absent today. This was the case all over the country. As late as 1990, when I started my practice in Oklahoma City, physicians, and surgeons, some of whom—like Norman Imes, who is in this room—moved their patients or threatened to move their patients to other facilities if the hospital didn’t provide what their patients needed. In Oklahoma City, Deaconess Hospital, right across the street from the huge Baptist Hospital, provided a quality check and ensured that both hospitals had to provide a quality experience for the patients and for the referring physicians. It was not uncommon for a physician to move all of his patients from one hospital to another until conditions improved. The Surgery Center of Oklahoma was successful early on due to the failure of area hospitals to provide orthopedic surgeons what they needed to care for their patients.

The role of the federal government in this power shift, away from patient and physician choice, is painfully clear and, once again, the obvious result of the auctioning of our consumer choices to the medical sellers. Medical sellers have been purchasing the choices of consumers and patients for a long time, and they are good at it. In Nashville a few weeks ago, a Washington insider told me the following story about the passage of Obamacare. Industry representatives and lobbyists had locked arms in opposition to Obamacare, assuming they would almost certainly be victimized by it. One by one, opponents were picked off. Those remaining and opposed wondered what was going on. The administration simply followed the money. Where were the biggest lobbies? The American Hospital Association, initially opposed to Obamacare, was told that their biggest fear, it seemed, was competition, primarily from physician-owned facilities. Therefore, if the AHA would support this law, Barry Soetoro (Obama’s real name), would see to it that new physician-owned facilities were banned and those in existence would be prohibited from expanding. The hospitals abandoned the opposition. The insurance carriers initially opposed, were promised a medical loss ratio, which would put all but four or five of them out of business. They, too, left the opposition. Last but not least, Big Pharma was told that it seemed their future profitability would come from biologic drugs, as the growth in generic drugs would eat into their margins. They were promised a twenty-year ban on competition from biologics produced in foreign countries. They, too, left the opposition, and the next week, the FDA [Food and Drug Administration] declared foreign biologics unsafe. As outrageous as this is, it is a broken record. Government intervenes on behalf of the few who can afford to buy their intervention, and the vast majority, the rest of us, pay the price. One incredibly disruptive intervention was when the federal government through its bankrupt arm Medicare decided to pay double for physician services delivered by hospital-employed physicians. It should come as no surprise that the percentage of independently practicing physicians has been on the decline ever since. This cynical move was meant to protect hospitals from the competition and demands for quality that physicians like Drs. Garrett, Allgood, Imes, and many others had made.

Currently, hospitals are no longer accountable to their medical staff, having purchased a large part of their staff, essentially making geldings of them all. Patients are now largely denied the advocacy they had in the past when independent physicians went to bat for them, voting with their feet. If a hospital was no good, physicians walked away. Now, if a hospital is no good, the hospital continues to see the flow of referrals from their kept referral sources, who are financially penalized for doing anything else. “Whose bread I eat, his song I must sing.” When someone asks me how I know free market facilities and physicians can provide quality, I tell them that referrals in a free market are not guaranteed, buyers can walk away.

I would argue that the quality of care delivered by a medical facility is directly related to the extent to which that facility is accountable to its medical staff. “What percentage of your medical staff is employed?” should be a question those attempting to measure quality should ask. To be clear, hospitals with employed staff do not have to be any good to retain business, a result of the corporate rather than physician control of patient care. Clearly, the root cause has been a shift in the balance of power, where the medical seller, the hospital, has gained the upper hand over the patient and their advocate.

This shift in power to the seller, in most cases the hospital, has become the new normal, and so ingrained in the industry that those who provide more efficient, cheaper, and better services are paradoxically criticized rather than applauded, as these fragile hospital systems might not survive a challenge to the fortress they’ve built. Not only has the balance of power been shifted, but any challenge to this balance also meets a swift and brutal response, usually on “fairness” and “social” grounds. When the late Tom Coburn, one of the Surgery Center of Oklahoma’s greatest defenders, was told by a hospital executive that it wasn’t fair to compare his hospital to the Surgery Center of Oklahoma, Coburn said, “You are right. They pay tax.” Tax advantages are one thing. Certificates of need, blacklisting by insurance carriers, and banning of physician-owned facilities by the Unaffordable Care Act: these are just a few examples of power granted to the sellers by the legislative concubines, always at the expense of the buyer.

This power shift has been with us so long that even those who claim to be free marketeers can get sucked in. Here is a comment at the website mises.org in response to a very positive article about a patient experience at the Surgery Center of Oklahoma. This comment is a tribute to the success of the hospital’s poor-mouthing propaganda campaign:

Interesting article but such a simple example of surgeries that were predictable and went as planned. Medical care can be much more complicated. Sometimes a surgeon finds the surgery is much more difficult than expected once it has begun. Complications after surgery can extend a hospital stay or send a patient back into the hospital as happened to my husband. People recover at different rates that probably can’t be predicted. My neurology surgery years ago was delayed six hours because the surgery before me turned out to be much harder than expected. If you get regular checkups there is no way to anticipate what lab work the doc may want and where that might lead, all affecting the cost.

Ah. The poor hospital, suffering with so much uncertainty. The author of this comment is not unique, having succumbed to the supposed plight of the seller, discounting the buyer’s role.

“In what other industry are the problems of the seller the buyer’s problem?” asks Jay Kempton.

How is it that craftsmen and others in the market provide quotes with the uncertainty they face? Many years ago, I solicited a bid from a carpenter to build a deck in my backyard. He made some measurements, asked what type of wood I had in mind, and gave me a bid. He encountered some difficulty setting his posts due to a rock formation not far under the surface, but this wasn’t his first rodeo, and he had made an allowance for this. Difficulties that he had encountered in the past were baked into his margin. If these difficulties didn’t materialize, he was more profitable. If they did, he had made an allowance. A margin based on the idea of a bell curve is not that difficult and is exactly how our prices are constructed at the Surgery Center of Oklahoma. Why are hospitals exempt from this discipline? Why is the uncertainty every other industry must endure intolerable in the medical industry? Or to the point of our message today, why are the difficulties of the seller of any interest whatsoever to the buyer or the public at large?

How can this ever change? This will change when the medical buyer, like every other consumer, lays true claim to his proper place and votes with his feet when treated with contempt. Hospital executives don’t worry about buyers with choices. They cannot fathom the idea that there is any such thing as a choice in an industry devoted to limiting choice. With their heads in the sand, drunk with arrogance, the time is now for buyers, particularly the self-funded buyers, to act. They can begin by understanding and embracing their rightful place and therefore the power they wield and then acting with confidence. As Matt Ohrt has said, “Quit feeding the beast,” and demand that sellers accommodate your preferences. As the awareness of our free-market movement spreads, the shift in power to the consumer is inevitable, a shift that is already increasingly visible.

The eternal challenge of government has been the subjugation of the many by the few, for if the few awaken to the government’s countless scams, the mass of people will become unmanageable and ungovernable. They will revolt. The challenge of the medical-industrial complex has also been the subjugation of the many by the few. The healthcare system in this country is not a disaster for everyone, after all. It is an orgy of robbery of the many by the few. Governments and this medical cartel use the same methods to maintain control, using fear, primarily. Fear, along with the purposeful placement of the seller at an advantage, and therefore placing the consumer and patient at a disadvantage, has kept the masses from rising up. Until now. The revolution has begun, and the traditional mold is crumbling. The alternative healthcare nation is within view. The time for the confident medical consumer has arrived, and the time has also arrived for price gougers and the rest of the bandits to fear a discriminating buyer and in enterprise recognize the customer as captain, as Mises did.