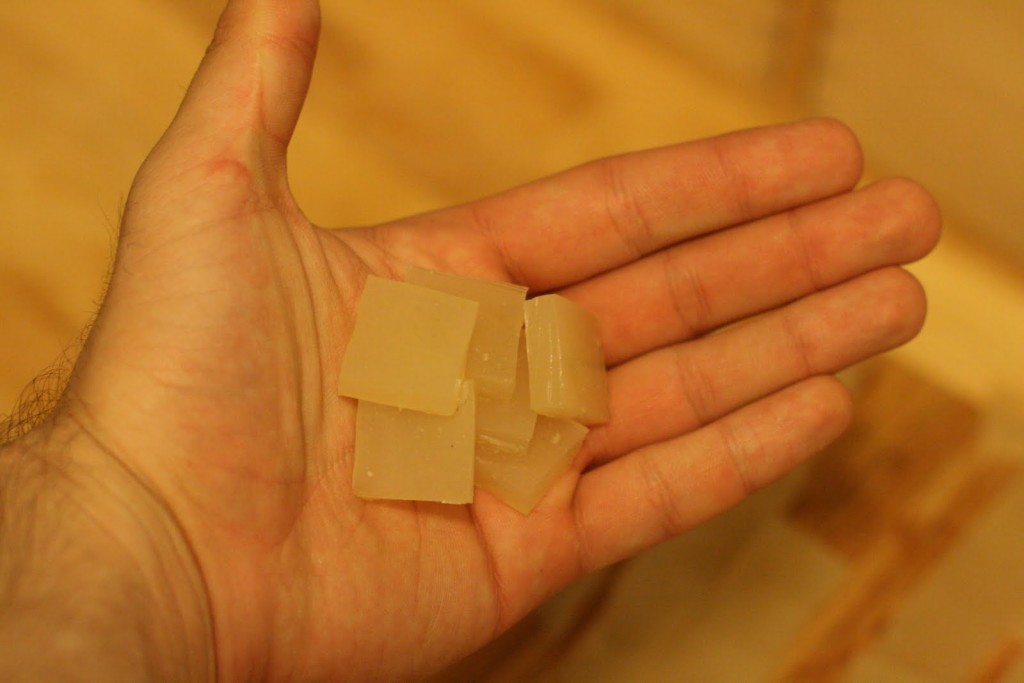

When it is soft, take it out and cut it into small pieces.

When it is soft, take it out and cut it into small pieces.

Put the small pieces back in the water and continue boiling it. Make sure the hide is always covered with water. The boiling will take hours, so you will have to periodically add more water so that the hide stays covered. Here I boiled it for three hours. The substance that you see on the side of the pot is overflowed liquid. When it dries, it becomes the glue.

Then strain out the hide pieces, or remove them with a spoon. Continue to boil the remaining water to reduce it down. I boiled it for another twenty minutes. Make sure to stir the liquid so it does not burn. By this point it should be getting fairly thick.

There is no specific required thickness. The more water it has, the longer it will take to dry once applied, but if it gets the job done, it is thick enough.

To preserve the glue, pour it onto a flat surface. I used a plate.

After about an hour, you should get a product which feels like rubber.

Cut it into smaller pieces and put it into a container. They should last quite a while, but since they are an animal product, eventually it will go bad. If you want to preserve it longer, spread out the liquid even thinner (less than 1/16th of an inch) and let it dry completely. The dried glue should be completely hard rather than rubbery. That way it should preserve longer.

To use the dried glue, just heat it up. You may want to add some water when heating it so it doesn’t burn.

That’s all there is to it. The glue will hold very securely when dry. Its most prominent historical use has been in the making of composite bows.

This time of year, we are looking for the younger, new growth plants which are typically the green plants among the dead brown.Here is a young cattail

This time of year, we are looking for the younger, new growth plants which are typically the green plants among the dead brown.Here is a young cattail