It was opening day 2019 as a trio of mallards streaked above the treetops of my favorite Pennsylvania trout stream. I could hear the rhythmic whistles of their wings, and looked down to see my springer spaniel shaking with anticipation. Two drakes and a hen banked hard and waffled down through the canopy. I mounted my battered Winchester ahead of the trailing drake, killed it, and swung past the hen to catch up to the lead greenhead, connecting on a true double. Cash made quick work of the marks. Without command, he dove back into his dog blind and resumed shaking. His eyes said it all: He wanted more. So did I.

But the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had recently elected to cut the Atlantic Flyway daily mallard bag from four ducks to two (only one of which may be a hen), and so our day afield was over in an instant.

The mallard is a relatively new duck in the East—compared to iconic birds like black ducks or canvasbacks—but it’s come to dominate game straps in New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Maryland and patches of other northern and mid-Atlantic regions. Mallards account for one-third to half the harvest totals in many of these states. Overall, mallards ranked second in the Atlantic Flyway’s duck harvest in the 2017-2018 and 2018-2019 seasons, behind only wood ducks.

Many hunters don’t fully understand the reasoning behind the bag reduction. And it is confusing, because in some Atlantic Flyway locations, mallards are plentiful. Surveys by U.S. Fish and Wildlife and studies conducted by conservation organizations such as Delta Waterfowl, where I work as managing editor, have shown that the eastern mallard population is in an overall decline, but according to some aerial survey data, specific populations are on an upward trend. There are still many unknowns since Atlantic Flyway mallards have not been studied with the same dedication and effort as Mississippi and Central Flyway mallards. It’s also possible that eastern mallards are doing well enough that there was no need for a bag reduction at all.

Understanding the Eastern Mallard Population

The first thing you need to know about Atlantic Flyway mallards is that they consist of two separately surveyed populations: those that nest in eastern Canada (plus Maine) and those that nest in the northeast United States (New Hampshire south to Virginia).

Here’s what the long-term survey data, most recently collected in 2019 (annual waterfowl surveys were cancelled due to COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021), makes clear:

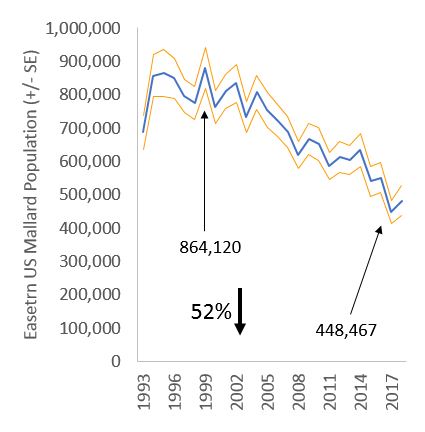

Aerial surveys show that Atlantic Canada’s mallard population has been steady or increasing since the eastern survey began in 1990, although it declined in the 2019 survey to 484,800 from a 2018 estimate of 585,000. Meanwhile, ground-plot surveys (conducted on foot by state and federal waterfowl biologists) indicate that mallards breeding in the northeast U.S. have been declining by about 2 percent per year since 1999. It was presumed that populations were growing in the region based on the mallard’s emergence in Atlantic Flyway harvest surveys. The data suggests this population accounts for considerably more ducks than the U.S. northeastern survey area. And its steady regression—a decline of up to 50 percent—led the USFWS to cut the Atlantic mallard limit in half.

Combined, the two populations put the 2019 eastern mallard breeding population at 1.05 million birds, 16 percent below the long-term average, and down from a high of 1.42 million in 1998.

“Compounding the challenges for waterfowl managers is the fact we know breeding mallards in the northeast United States have declined since 1999, but that’s when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began more extensively surveying them,” said John Devney, chief policy officer for Delta Waterfowl. “The data prior to then is pretty limited. What were the northeast U.S. mallard numbers in the 1970s and 1980s? Was the population at its peak in 1999? If so, that could mean the decline is simply the birds resuming their normal carrying capacity rather than suggesting some big crisis.”

Delta has partnered with the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry to undertake key research on eastern mallards. Although mallards have been studied extensively on the U.S. and Canadian prairie, data on eastern mallards is scarce, though that is changing as flyway biologists and waterfowl managers have begun to undertake a massive radio collar program. The data from this program will hopefully reveal more about the habits of Atlantic Flyway hen mallards in the years to come. Compared to mallards farther west, especially the mid-continent population that feeds the Central and Mississippi Flyways, the Atlantic population’s demographics are still a mystery.

“The Atlantic Flyway has taken a distant backseat in the waterfowl-research world,” said Dr. Michael Schummer, a renowned biology professor at SUNY-ESF and avid duck hunter. “For most people on the East Coast, the mallard is the No. 1 duck in the bag. We need to solve this problem, or we’re in trouble.”

Rethinking Band Report Data

On the upside, there’s a broad database of band reports for wild eastern mallards. That database allows biologists to have a better idea where mallards are hatched as long as they are banded when they are too young to fly (not all waterfowl are banded at that stage of life). In partnership with SUNY-ESF, Delta is also studying stable isotopes in the flight feathers of juvenile mallards shot or banded in the Atlantic Flyway. Stable isotopes are biological markers locked in certain bodily elements, such as human hair and waterfowl feathers. Their analysis provides the ability to determine where a duck was hatched with surprising precision. The groundbreaking effort allows for a better understanding of the eastern mallard’s decline and identifies its most critical breeding areas.

“Conversations with the Atlantic Flyway technical staff made it clear they had a major research priority: Determining the relative contributions of eastern Canada versus eastern U.S. mallards to production and hunter harvest,” Devney said. “That would improve their understanding of the overall decline and better inform future decisions on hunting regulations. Stable isotope research holds the answer.”

The information will be used to boost production of eastern mallards, and hopefully pave a way to increase the Atlantic Flyway bag limit.

“Our goal isn’t just cool research,” Schummer said. “But strong, actionable science that matters and should hopefully be applied.”

The analysis of thousands of wing feathers has refuted a common assumption — that the vast majority of mallards shot by Atlantic Flyway hunters in America were hatched in the northeast United States. Stable-isotope research indicates the inverse to be true. A whopping 64 percent of mallards shot in the U.S. Atlantic Flyway were hatched in Canada, while 36 percent were hatched in the northeast U.S.

Why the discrepancy? Presumably, Schummer says, many of Canada’s eastern mallards are migrating across the border as early as September — far sooner than thought — and being labeled U.S. ducks during banding operations.

“The banding data will tell you that the mallards shot (in the eastern United States) are coming from the States,” Schummer said. “So, while New York says 68 percent of the mallards it shoots were produced within the state, a way to say it more accurately might be that 68 percent of the banded ducks it shoots were banded within the state.”

That finding alone has potentially massive ramifications. After all, mallard limits were slashed due to the indication by USFWS harvest models that waterfowlers were putting too large a dent in the declining northeast U.S. population, particularly among adult hens. Should the Delta/SUNY research stand up to peer review—a process expected to begin in spring 2022—the Atlantic Flyway Council will have to consider that East Coast waterfowlers are largely hunting the stable, eastern Canada population.

“It may prove that we have far fewer breeding mallards in the northeast United States than we believe, and that Canada has way more than we think, plus good production,” Schummer said. “We may not have a problem. We may not have a mallard problem in the East at all.”

Pen-Raised Mallards Have Infiltrated the Flyway

Mallards nesting in eastern Canada are presumed to have spread east from their traditional prairie breeding grounds, given their aggressive and adaptable breeding habits. However, mallards breeding in the northeast U.S. are thought to have resulted from the release of ducks bred in captivity. The practice of raising and releasing mallards began in the 1920s and became common in the 1980s among game farms and private shooting preserves, when a drought-induced population crash occurred for many waterfowl species. The number of domestic mallards that have made it into the wild is unknown. It’s likely a majority of them are shot at the preserves, but some do escape. The practice of releasing mallards still continues today at game preserves, but on a smaller scale.

“Despite the lack of organized banding records, there is pretty strong anecdotal evidence regarding the ebb and flow of mallard releases in the Atlantic Flyway,” said Dr. Chris Nicolai, a Delta biologist . “The consensus among biologists is that the practice grew quickly following World War II, likely peaked during the drought years of the 1980s — when an East Coast mallard, or any mallard, was hard to come by — and dropped significantly by the year 2000. There are still domestic-strain mallards being released, but not nearly on the level they were 40 years ago.”

But these released mallards were not North American greenheads, they were European, domestic ducks. They look like wild mallards, but genetically, they are 10 percent different than North American mallards. That’s a huge gap, considering that American black ducks are only 1.5 percent genetically different from our continent’s native mallards. Game-farm mallards tend to have slightly shorter bills, perhaps an adaptation to nibbling barnyard corn and pellets rather than plucking underwater vegetation. And there’s anecdotal evidence, says Nicolai, that the European-gene hens are less-devoted mothers, far less driven to incubate their eggs for adequate periods throughout the day.

“In my opinion, there were two key missteps that took place that are really hard to fathom given the brilliant waterfowl scientists at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service during the heyday of game-farm releases,” Nicolai said. “For one, everyone is so careful when stocking trout and other species to avoid contaminating the North American populations, so I have to wonder why European mallards were allowed—why not at least release true North America-strain mallards? And secondly, despite the millions of dollars the government spends on duck banding research, the released birds were generally tagged by private duck clubs. Often there wasn’t even a phone number or address to report the bands. We therefore have zero data on the migration, reproductive success, survival or hunter harvest of the released birds.”

SUNY-ESF is collecting blood samples of eastern mallards to identify their genetic origins. The study will reveal the extent to which the ducks breeding in the northeast United States are of domestic stock, and the degree to which hybridization has occurred between game-farm ducks and native, wild mallards.

So, is the harvest discrepancy in the banding data caused because Canada, in reality, has a larger proportion of eastern breeding mallards than previously believed, or is it because the nesting effort among ducks in Canada is more productive?

“I think it’s both,” Nicolai said. “Canada has far fewer domestic-strain ducks, which likely means they’re more productive. Game-farm birds tend to do lousy in the wild. And the research is clearly suggesting that we were banding birds in the northeast United States and calling them U.S.-born ducks when they’d in fact migrated early out of Canada. Additionally, mallards hatched in America may be tougher to hunt, because they tend to stick to parks, golf courses, and other areas where you can’t sling decoys. They’re kind of like resident Canada geese in that regard.”

Domestic Eastern Mallards Aren’t Breeding Other Species Out of Existence

Some biologists contend that our cherished mallards—across all four flyways—are prolific to a fault, imperiling other species with their aggressive breeding instincts and tendency to hybridize other species. Feral mallard genetics are a threat to black ducks, Hawaiian ducks, and mottled ducks. Up to 12 percent of Florida’s mottled ducks are estimated to possess mallard genetics.

“It’s certainly a problem,” Nicolai said. “But for black ducks, the threat isn’t as grave as many of us biologists first believed. When I first saw the data in the 1980s, I thought black ducks were doomed to be hybridized out of existence by mallards. But here we are in [2022], with a limit that’s increased to two black [ducks] daily and we’re sustainably shooting more than we have in 30 years. What’s lost here I think is we’ve got a real success story. Canada’s eastern mallard population is stable. Black ducks are stable. And there are a reasonable number of breeding mallards in the northeast United States. Just think if the released mallards exploded in their non-native habitat in the same way European starlings have. Now that would be a problem.”

Since the released mallards haven’t significantly infringed upon the health of other Atlantic Flyway waterfowl, and duck hunters hold greenheads in such high regard, it makes sense to try and save the species, invasive or not. After all, the ring-necked pheasant, rainbow trout, and Hungarian partridge—species many hunters and anglers are passionate about and rely on each year—don’t exist solely in their original ranges. No one wants to rid the prairies and streams of those animals or fish. Why not save all eastern mallards?

“A few generations ago it was rare to spot a mallard in the Atlantic Flyway,” Devney said. “But now they’re all over, and people like them — because after all, mallards are not a hard sell. They’re amazing birds.”

Read Next: Our Obsession with Greenheads Is Ruining Duck Hunting as We Know It

Will the Mallard Limit Return to Four?

Ultimately, Atlantic Flyway duck hunters want to know when (or if) mallard limits will return to four birds per day, but there’s no timeline for that at this point. Migratory bird population health is delicate. One year a species can be abundant, and the next it can have poor nesting success. For now, the two-bird limit remains in place, but eastern mallard numbers are trending in the right direction.

“I’m confident we’ll get back to four mallards in the East,” Nicolai said. “It could be habitat work or a sudden increase in survey numbers that gets us there, but even more likely, it’ll be a change in the ‘risk threshold’ of the USFWS harvest models driving regulations.”

That move would not be unprecedented. Less than two decades ago, new research into the impact of hunter harvest allowed the canvasback season to reopen across all four U.S. flyways. And the USFWS recently determined it had been overestimating the pintail harvest by 250 percent, which could lead to increased limits on sprig as well.

“The Atlantic Flyway is investigating a ton of banding data and has smart people exploring eastern mallards,” Nicolai said. “There’s a lot of room to tweak the harvest model incorporating new knowledge.”

That information continues to be sought by Delta Waterfowl and Dr. Schummer’s students at SUNY-ESF.

“Delta Waterfowl is hard at work to get eastern mallards back on track,” Devney said. “We are committed to answering key questions about Atlantic Flyway greenheads.”

Kyle Wintersteen is the Managing Editor for Delta Waterfowl Magazine. He lives, works, and hunts in central Pennsylvania with his English springer spaniels.

The post New Research Shows Atlantic Flyway Mallards Actually Might Not Be In Trouble. Was the Bag Limit Reduction Unnecessary? appeared first on Outdoor Life.